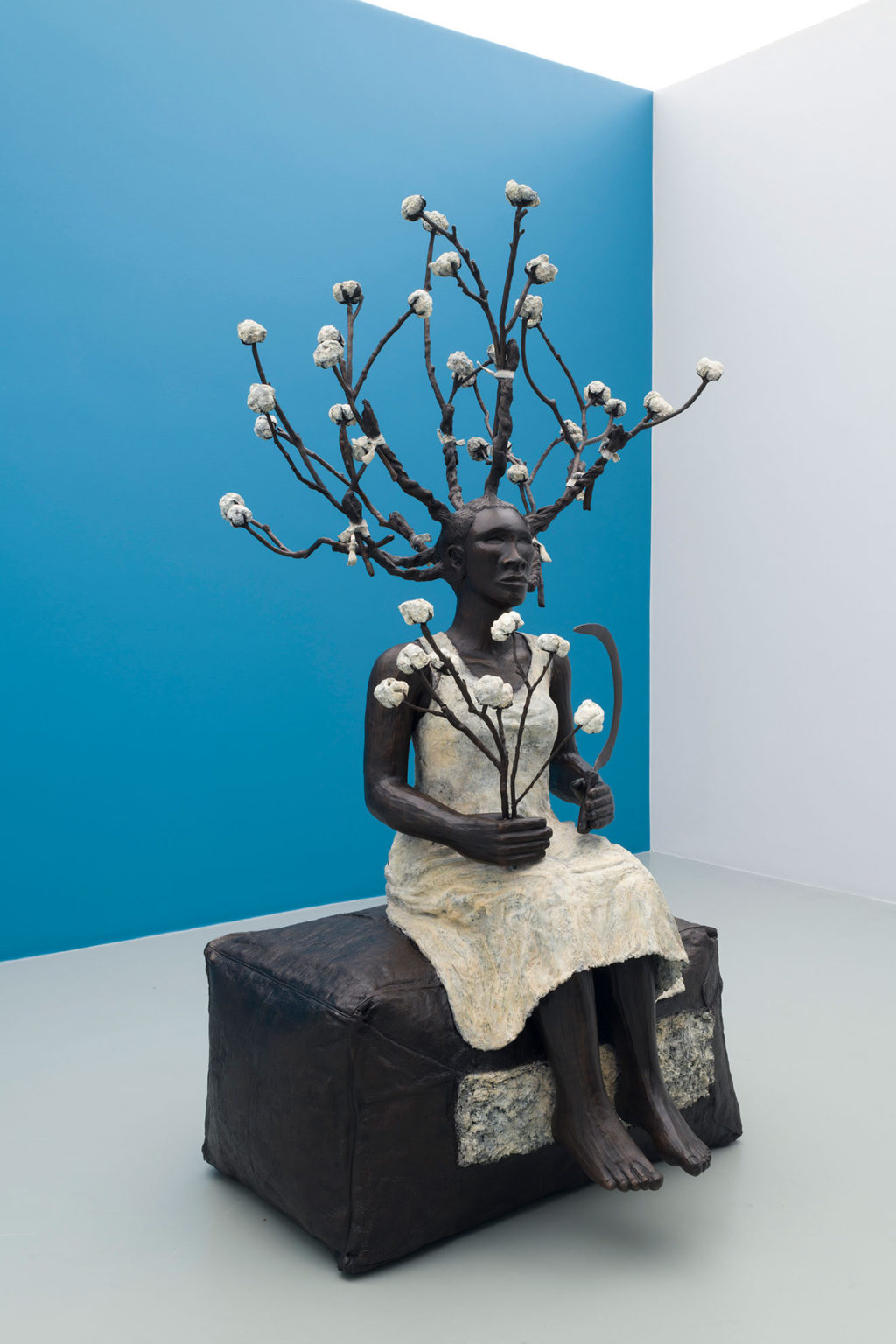

The current Alison Saar (NA 2011) exhibition at LA Louver in Venice is small, consisting of a single work—Grow’d. Yet, it is a testament to Saar’s prowess that the piece could be discussed for hours. It packs a big punch. Wrapped up in this life-size bronze sculpture are references to turn of the century literature, the Civil War, the civil rights movement, watching her daughter grow, an examination of the psyche of children growing up in the US today, and an intention to empower women and Black communities.

Grow’d depicts a female figure, Topsy, sitting on a bale of cotton like a high priestess. She holds the tools of the labor of her people—a sickle in one hand, cotton grasped in the other. Branches of cotton braided into her hair extend upward, referencing a narrative from Saar’s previous show with the gallery, Topsy Turvy, in which branches of cotton were tied to adolescent Topsy’s hair and her army of enslaved children, to help disguise them as they snuck through cotton fields to attack their masters.

“Often [priestesses] have their hair done in really amazing hairdos which also have a narrative about who they are, their echelon, their height in society. She’s festooned, but it is also a warlike kinda thing… She’s definitely armed and ready for anything that comes her way again.”

This is Saar’s revision of Topsy as a fully-grown woman, now in control of her destiny. Topsy, a character heavy with over a century of negative associations from Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1852 vital anti-slavery book Uncle Tom’s Cabin, was initially introduced to Saar through post-abolitionist stereotypical views that presented Topsy as goblin-like. Saar’s portrayal of Topsy has always pushed back against those visual cues in favor of Stowe’s intention to paint a positive picture of enslaved people. “If you look at early lithographs, they’re not super derogatory. Her hair is in pigtails. Later on, the change really came through media—through print and film.”

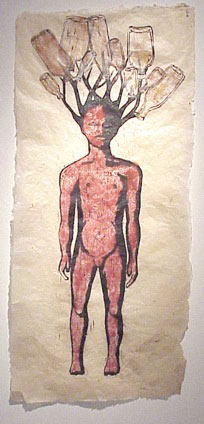

The first time Saar visited Topsy in her work, she asked her five-year-old daughter to pose for her. “My daughter was very sassy and very opinionated. I loved this idea of a youthful naiveté and wisdom, combined.”

Reclaiming Topsy as a hero was an essential element of Topsy Turvy, as Saar tried to imagine what the experience might be for African American children and young girls growing up in today’s nation, still ripe with daily traumatic events in the form of continued racism and violence against women and Black communities. Saar relates to the experience, as it reminds her of her own youth during the civil rights movement. “There were a lot of people on the streets protesting, but there was a lot of police brutality… In some ways [the work] becomes autobiographical in that I’m kind of—almost reliving. Trying to recall how I saw those things when I was five or six years old.”

One of the most striking installations in Topsy Turvy was an army of young female slaves, rendered in bronze, weaponized and ready for war—inspired in large part by the 2016 murder of Philando Castile by a police officer. In a video taken after Castile was shot seven times, Castile’s girlfriend’s daughter could be heard saying, “I don’t want you to get shooted… I can keep you safe.”

“That really struck me again to think about how these kids… how do they psychologically survive this trauma? Whether it’s happening to them personally or to people they know, it’s all over the media, and how do they not feel threatened as really young children walking down the streets? In part, I wanted to put some powerful mojo out there to empower them.”

While Saar admits that there is still plenty to be angry about, she believes recent media attention to issues perpetuating the inequality of Black communities has ignited a collective strength, and movement forward along the arc of justice. “It’s been going on all this time, but the media is what has made it accessible.”

Saar’s work and Grow’d can be seen as a preservation of history; proof of this revelatory and violent time when, “there’s no hiding from it, or denying it.” This moment in 2019, when women and Black communities are yet again empowered to stand their ground, won’t be forgotten 100 years from now—not if Saar has anything to do with it.

“I think art is sometimes not a truer history, but a history that’s more emotive and emotional,” says Saar. “It’s important in terms of seeing how people are responding to what’s happening.” Too often, history is written by the winner—but, as Saar has proven, art as an uncensored mode of expression has the power to reveal what is unseen; to serve as evidence of a true human experience when words or photographs simply won’t convey the emotional reality.

Grow’d is presented at LA Louver gallery in Venice, CA, from February 27 – March 23, 2019.

Bianca Collins is “The Art Minion” columnist for Artillery Magazine, and the Editor of KCRW’s “Art Talk” with Edward Goldman. She works hard to make the fine art world more accessible through arts journalism and cultural event production. Follow her on Instagram at @artminion_.