During the summer of 2018, the National Academy of Design’s former school had just gone on hiatus and people were wondering how to use the classrooms before vacating the building. It was a fortunate occasion to experiment with different models of how to be a school, and perhaps rethink how pedagogy should exist within the Academy. I thought it could be exciting to hand the place over to a young collective who would draw from a variety of communities in a spirit of festive turbulence and disciplined creativity.

I became aware of Bomb Pop!Up when it took over a house in Brooklyn a couple years ago and filled it with art, performances, and a dance party over the course of a weekend. Two of its members, Gaby Collins-Fernandez and Drea Cofield, are former students of mine and impressive artists that I respect and admire for their extravagant energy and initiative. Jonah Parzen-Johnson is their musical director and brilliant sax player. I asked if they could do something; they said yes and thus I became something like a collaborator/producer/participant in their three days of performances, workshops, and exhibitions called How To.

So, in order to keep the spirit of the event alive, I invited Drea, Gaby, and Jonah over to my studio so we could talk about what happened and what it all meant.

David Humphrey: I’m curious how each of you would describe that extravaganza at the National Academy of Design.

Drea Cofield: How To was Bomb Pop!Up’s first institutional project, and we had to scale up our programming in relation to the context and theme. We have made two other large-scale productions, as well as many smaller events, and while all of them included art, music, and discussions, this was an opportunity to do something specifically pedagogical. Gaby and I discussed using a reduced concept of a school, “how to,” as a way of linking the Academy’s history as a teaching institution with experimental and egalitarian art practices and methodologies.

Gaby Collins-Fernandez: I recall the experimental, even provisional, nature of how it developed. David first brought up the possibility of doing something at the NAD on a subway ride, and he pitched it as a kind of mini art fair. One of the strengths of BPU is that ideas develop and accumulate both fluidly and with momentum.

Cofield: There are only three of us, and we have different, yet complimentary, backgrounds and skills. Gaby and I usually brainstorm and come up with a theme, which grows swiftly into a format, and then we talk with Jonah about how to integrate music and performances practically and structurally. We surprise each other a lot, and treat each project as an occasion to push our boundaries and highlight artists that we admire.

For the NAD, we were thinking: how can we curate an art show, music, and workshops according to a theme which is a pedagogical idea; have this concept allow participating artists freedom in their approach and programming; address the “Traditional Art Academy” as a type critically; and also have a lot of fun?

Instead of using the Academy as a means to teach traditional art skills, we wanted to allow instructors to build workshops according to their specific curiosity and expertise.

Humphrey: Your idea was closer to what they asked for, which was a workshop. The event could have been the cartoon of a workshop, or a series of cartoons of workshops, but it turned out to be much more than that.

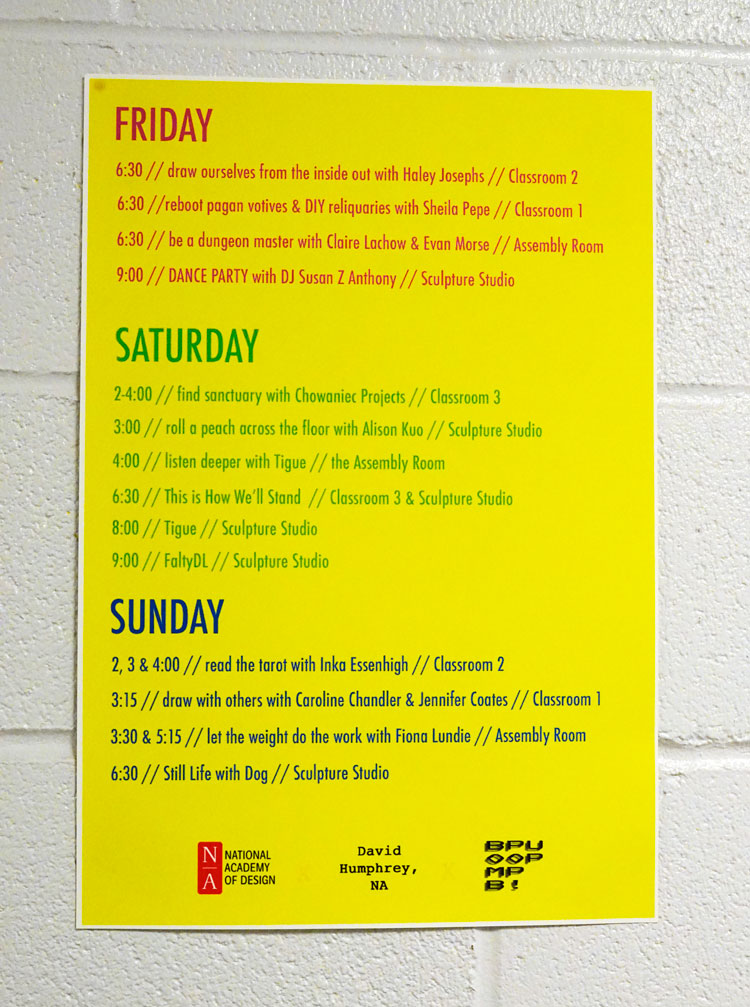

Collins-Fernandez: We settled on doing a three-day weekend, with three workshops and musical performances on each day. It ended up that they were both very practical and extremely esoteric, from learning how to read the tarot (with Inka Essenhigh), to learning how to make food art (with Alison Kuo), to learning how to think about experimental percussion (with Amy Garapic, Matt Evans, and Carson Moody of Tigue), etc.

Humphrey: I took almost all of those workshops and I found each and every one exciting: drawing the body from the inside, who knew? Food art that could be destroyed at the end. Of course, improvising with Jonah and his crew with the band Tigue was one of the high points of my life.

Collins-Fernandez: So far! [Laughter]

Jonah Parzen-Johnson: One of the appeals of BPU is that we balance understanding and knowledge with absolutely no understanding and knowledge.

I’ve always wanted to collaborate with artists, but often found that if you lack the vocabulary and the background, it is impossible to be involved. BPU isn’t afraid to figure out how to do things while they’re doing them.

When I’m creating music ideas for the BPU events, I try to think of ways to take things that require a certain base of knowledge and then present them to people without that base of knowledge. I hope that they’ll have the same musically welcoming experience that I have visually.

Humphrey: That sounds like you are extending the improvisatory social form of your music outward to an institutional setting.

Parzen-Johnson: I believe that esoteric and complicated things don’t have to be inaccessible. Just because there’s a lot of process underneath something doesn’t mean you can’t understand it and enjoy it. The least esoteric workshop to me was “How To be a Dungeon Master” (with Claire Lachow and Evan Morse). I wasn’t afraid to not understand fully what was going on, and still felt like I could learn or gain something from the experience. How To was simultaneously events for artists and events for people to be among artists.

Collins-Fernandez: We’re trying to create a space for musicians and visual artists to have experiences, or even stumble unwittingly into experiences, that they might not have sought out.

Humphrey: That’s not the goal of the traditional form of an academy. BPU became a kind of anti-academy, entering the organization as a foreign agent.

Collins-Fernandez: We were trying to figure out how to create an “academy” that would develop from the specific knowledge of practitioners. It’s not thinking about an academic structure as the purveyor of expected learning, but rather thinking that we learn best when we’re being taught by someone who cares a lot about what they’re teaching.

Humphrey: I guess that’s the utopian aspect of How To, in which pedagogy takes place in a speculative space with no anticipated results.

Except, perhaps, fun.

Collins-Fernandez: Right! [More Laughter]

Cofield: The teaching artists or National Academicians would be learning as much as those participating in the workshop.

Collins-Fernandez: I think this also applies to the artists who made works for the group show that accompanied the workshops. There were a number of artists, like Leeza Meksin and Tracey Goodman, who were in the trenches with us, figuring out how to adapt their works to the peculiar spaces of the empty classrooms in the basement. They took a leap of faith.

Humphrey: It was building on the vestiges of the National Academy’s school, like Lebbeus Woods, who tried to embrace tectonic or social turbulence with his architecture. Astonishing buildings were imagined by him for earthquake or war zones.

Cofield: Like the adapted reuse of industrial spaces for dramatically different purposes, as opposed to really institutional spaces that have their own stubborn identities.

Parzen-Johnson: If you look at galleries or music venues, you always see a situation where the venues or the galleries are forced to bend to the concept and aesthetic of the artist. That art can be created in the context of what people are experiencing at the moment is a very generous version of performance and presentation at the heart of BPU.

Humphrey: That’s beautiful. How To is a generous pedagogy that leaked out in all directions. Suddenly everything became How To-able. Every artwork, every occurrence and conversation could be interpreted as the arrival of a How To moment. Could we derive from this a speculative philosophy or politics?

Parzen-Johnson: BPUism?

Humphrey: You teach by example, so how to be BPU becomes an organizing principle. You make events in order to figure out who you are as a collective entity.

Collins-Fernandez: I’ve certainly learned a lot about how our dynamics work and how we can rely on each other in shifting situations, like any collaboration. There’s something explicitly open-ended about what “BPU” is, which is also facilitated by the idea that the events are short, not intended to be forever; always fleeting.

Cofield: The nature of the temporary, the pop-up spirit, is that it’s always changing, both in terms of context and scale.

Humphrey: So I guess you’re in the business of coming up with opportunities, making proposals, but also adapting to unexpected occasions.

Parzen-Johnson: The shows are explosive. They’re not smoothed—not like a pop-up art exhibition in the lobby of an office building. In a very quick moment, it’s there for everybody near enough to experience, and then gone just as quickly before anyone can fully understand what happened.

Cofield: Including us! I want to return to the aesthetics and viewership of How To, to thinking about it as creating an expectation that artworks can actually teach you something. I was thinking that something is wrong with the prejudice against didacticism in artworks, because it seems to say more about an audience that’s resistant to learning than it does about the artwork itself. Why is it that you would look at a piece and say, “It’s didactic. I hate it.” Because we all hate school?

As opposed to considering the creation of a structure where viewers are receptive to the idea that everything has an internal, abstract, literal, ephemeral, structural sense of what it is trying to tell you, or show you, or teach you. How To is a playful way of engaging with the transmission and reception of teaching and learning.

Humphrey: You have boiled out the bossy, hierarchical character of didacticism that people object to. I think you are talking about a conversationally non-hierarchical, emergent didacticism.

Parzen-Johnson: Yeah, but isn’t it institutions that are hierarchical? Learning and teaching don’t necessarily have to be hierarchical until they become a source of employment with an infrastructure. If BPU is inherently non-institutional, then it has an opportunity to be more generous and egalitarian.

Collins-Fernandez: This conversation has special relevance to Ilana Harris-Babou’s piece, Finishing a Raw Basement. Her work allows us to understand what a tool is and how it works. We have a ceramic hammer that doesn’t work, but we learn how to make this hammer, or something like it. Her works articulate what the tools are and how they may be important, but also deny their factual tactical tool-ness. BPU’s How To pedagogy is similar.

Cofield: Within the context of the show, the didact could be any work or any person, both simultaneously and possibly in contradiction. Having a workshop is like having an opinion and sharing it with people without worrying about its rightness or wrongness; being correct and incorrect.

Humphrey: Can we call it an experimental way of organizing social energies?

Collins-Fernandez: That’s right. Which is why we try to end each day with a social event and music. For me, How To’s climactic moment was in the transition from Jonah’s ten-piece improvisational set amongst the artworks to Tigue’s more formal performance, culminating with dancing and a DJ. We tried to make opportunities for people to be with one another amongst art without a formal opening reception.

That improv set wasn’t in any kind of sanctioned music space. It took place in a room with three subdivisions, which forced unfamiliar proximity with the musicians as we moved through it. There was an initial and intentional obstacle for the audience because you could not see all the musicians from any vantage point and they, also, could not see each other—so we all had to figure out how to play, listen, and be there as it was happening.

Parzen-Johnson: Audience members had to stand very close to the musician they decided to watch. It was like you were pledging allegiance to the musician closest to you and experiencing the entire performance from their perspective. The only way to experience the music from a different perspective was to actually walk to a different part of the room. I wanted to create more opportunities for the musicians to specifically engage with the artworks, so I chose a different piece for each musician. Some people felt comfortable receding backward and letting the audience walk by them as if they were a sculpture. Others were much more sensitive to having the audience close to them and changed what they were doing, getting louder and quieter in response to audience movements.

Cofield: What a beautiful metaphor for the whole thing.

Humphrey: The event generates an explosion of descriptions that don’t match each other and go forth to have their own, independent lives.

Parzen-Johnson: Everything is about learning how to listen to other people’s perspectives, trying to understand them, and not being too hard on yourself when you don’t get it.

I try to approach our projects with the same philosophy of citizen/civilian participation that I have in my political activism. If every artist was an arts presenter—if every arts presenter was an artist—then you’d have a much more balanced and inclusive society than if everybody staked out a position and said, “I’m on this side, you’re on that side, and there’s no way for us to work together except in this siloed context.”

Humphrey: What would you call it? This is surely wrong: Libertarian Collectivism?

Collins-Fernandez: No. We renounce that word. [Raucous Laughter]

Humphrey: Anarcho-Citizenship?

Collins-Fernandez: Better.

NAD x David Humphrey x BombPop!Up: How To was presented at the National Academy of Design June 15 – 17, 2018.

David Humphrey (NA 2015) is a New York artist who has shown nationally and internationally. He has received a Guggenheim Fellowship and the Rome Prize, among other awards. An anthology of his art writing, Blind Handshake, was published by Periscope Publishing in 2010. He teaches in the MFA programs at Columbia and is represented by the Fredericks & Freiser Gallery, NY.

BombPop!Up is the artist-run initiative and social practice of Brooklyn-based artists Drea Cofield, Gaby Collins-Fernandez, and Jonah Parzen-Johnson. Launched in the summer of 2016, Cofield and Collins-Fernandez create dynamic platforms and recurring events that bring together local, emerging culture-makers operating in different spheres (art, music, dance, education, social activism, etc.) in a space that is inclusive to a larger public. Parzen-Johnson, a contemporary baritone saxophonist, became involved early on as a collaborator and music director. BPU has organized three large productions to date: The Bomb Pop-Up! Show, a three-day, three-story art and music show in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn; BPU02: I Want to Believe, a six-day art show with music and social programming at the Coustof Waxman Annex on the Lower East Side in Manhattan; and BPU: How To, with David Humphrey and the National Academy of Design. BombPop!Up has also participated in an art and music residency—BPU Presents—at Pete’s Candy Store in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, since May, 2017. Each production is accompanied by a print project, including contributions by all participants, to serve as indexical memorabilia of the event. BPU is committed to working with organizations and groups that promote and work towards equal rights and progressive values, and strives to create an inclusive, intersectional, and safe space for all.