The origins of theater date back to the 6th-century B.C. in the area of Ancient Greece where Dionysus, the god of wine, arts, and parties, was celebrated. In theatrical representations performed in his honor, all the actors were men, hence the importance of costumes and masks worn to play characters of different ages and genders. These performances took place in the hemicycle, designated as a “theatron,” which means “the seeing place.” Today, Cindy Sherman (NA 2012) uses all these codes, from dramatic or satiric dressing, to often-exaggerated makeup, masks, wigs, and implants, offering a contemporary aperçu of the legacy of this seeing culture. The Louis Vuitton Foundation in Paris is giving the artist an exegetical retrospective, regrouping some 170 works produced between 1975 and 2020 and articulated in 18 sections, on view through January 3.

I visited the show in September, when the Foundation was still open. Due to COVID-19, French museums are temporarily closed. Luckily, the Foundation is now offering 30-minute live tours, allowing you to safely see the exhibition from home.

Early Aesthetics, Cinema, and Male Gaze

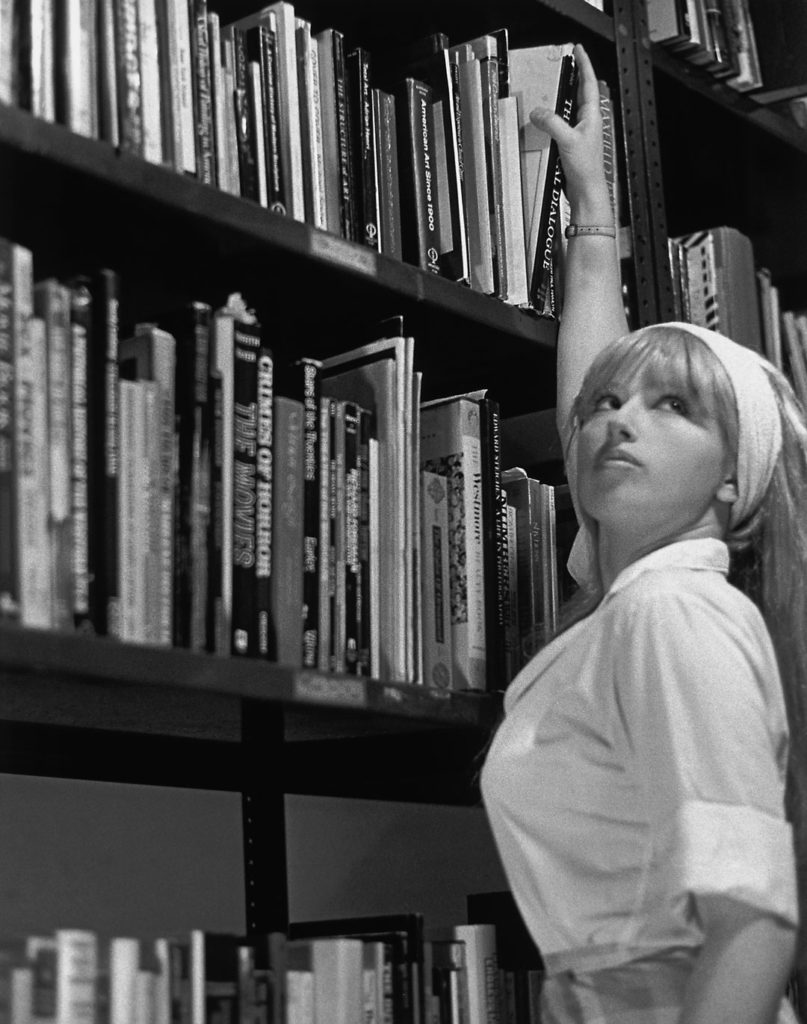

What struck me most with this retrospective was the large variety of references Sherman uses to contextualize her work. The show begins with her Untitled Film Still series, made in the late 1970s, which caught the attention of the art world. A film still is a photograph taken on or off the set of a movie or television program for promotional purposes. A woman waits alone for someone on the road at twilight, her suitcase at her feet in Untitled Film Still #48. A housewife complains about the weight of her shopping bags she just dropped on the floor in Untitled Film Still #84, while another stands in front of the library, grabbing a book without paying attention, scowling at someone out of frame in Untitled Film Still #13. All these images seem familiar, and we can easily picture them drawn from Alfred Hitchcock, Stanley Kubrick, or nouvelle vague movies—see Brigitte Bardot in Le Mépris (1963) by Jean-Luc Goddard or Jeanne Moreau in Ascenceur pour l’échafaud (1958) by Louis Malle. But they aren’t. The genius of Cindy Sherman is her ability to give us an impression of déjà vu within these imagined heroines depicted in black and white, all while building a dialogue about stereotypes of the representation of women in the 1950s and 1960s and the male gaze they were subject to. She enfranchises her characters from the male gaze actresses were subject to, giving them unexpected roles such as a librarian in Untitled Film Still #13. At that time, Sherman had just moved to New York after graduating with a bachelor’s degree from the State University of New York College at Buffalo, but her aesthetic identity was already substantial and exclusive.

Old Masters/Contemporary Views

As I walked through the exhibition, I found myself spending a large amount of time in the History Portraits section, made while Sherman was living in Italy in 1989. The series was eventually presented in a Metro Pictures Gallery show in New York, which was largely acclaimed by both critics and the public. The artist reinterprets old master paintings from the Renaissance and Baroque eras, adopting the conventions of postures, colors, and even framing with massive golden or ebony frames. Sherman’s early film noir works from the 1970s and 1980s are gone, and she quickly begins to consecrate her work to more provocative and deliberately ambiguous portraits. Unlike her Untitled Film Still series, we can recognize specific paintings in these photographs, such as Young Sick Bacchus by Caravaggio in Untitled #224, the Melun Diptych by Jean Fouquet in Untitled #216, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’s Madame de Moitessier in Untitled #204, or Raphael’s La Fornarina in Untitled #205. In all we see Sherman’s prodigious ability to play with images and representations.

I could not move on after encountering Untitled #228. Defying the viewer with bloodshot eyes but a placid face, standing in front of richly printed textiles and wrapped in a sensational red satin dress, Judith presents the head of Holofernes in one hand, while in the other she holds the sinful knife. Judith is a popular biblical figure often painted during the 17th-century. She is known for saving her town Bethulia from an Assyrian general by seducing and then killing him. Some versions recall that she was actually raped by Holofernes. The popularity of the subject gained critical importance when the artist Artemisia Gentileschi painted the scene twice (see here and here), using herself as a model to depict the heroine after being raped by her private teacher and mentor, the painter Agostino Tassi.

I was not surprised to see Cindy Sherman embracing this proto-feminist leitmotiv, important for both history and the history of art, and delivering an engaged and profound piece. But while Judith is commonly assisted by her servant in most representations of the scene, in Untitled #228 Sherman stands alone, similar to her way of working as an artist: all by herself in her studio, without any assistants, putting the viewer in front of the fait accompli in real life as in fantasy.

Deconstructing the Nude Body

In 1992, Cindy Sherman revealed to the world Sex Pictures. Even though the body is still at the center of the works, the artist no longer appears in it. Distorted, adorned with implants or animal attributes, painted, perforated with unknown objects—some of which are perhaps better to not know about—the photographs disquiet as much as they fascinate. To create this magistral performance you won’t be able to get out of your head, Sherman ordered study mannequins from a catalogue dedicated to medical studies. In a beautiful essay about the artist, Calvin Tompkins recalled that, “Her sex pictures were in some sense a response to the political storms over ‘pornography’ in art (Jesse Helms versus Robert Mapplethorpe, et al.), and also to Jeff Koons’s copulation images, which she had greatly disliked. (She found them puerile and sensationalistic.)”1

Once again, there is a thin line between what Sherman shows, what she thinks, and what she means within her photographs. Some may see Surrealist references, such as Hans Bellmer’s anamorphic dolls, in this series. I see the natural extension of Sherman’s very own interrogations around body and identity. The large formats confront the viewer with life-size hybrid humans. What is normal? What is real and what is not? We feel uncomfortable perceiving them because they are presented and impose themselves at the same level as us, and suddenly our benchmarks are muddled. To serve this purpose, the scenography creates intimacy by showing the photographs in a separated section, as an alcove where secrets are told and intimate scenes take place. Here, visitors can properly enjoy the works, and the anti-erotic sex dolls become the receptacle of the viewer’s own emotions.

Back to the Medium

Cindy Sherman is a technician. Each work she produces is maniacally organized, artistically controlled, and ordered. Her aesthetic rigor, the variety of techniques she uses and masters are just some of the reasons why we can consider her as one of the most important photographers and contemporary artists of our time. The Louis Vuitton retrospective embraces this recognition by showing a wide variety of the artist’s techniques.

In her Untitled Film Stills and Early Works series, Sherman uses gelatin silver prints to heighten a grainy appearance and establish a vintage ambiance. She also employs rear projection, a special cinematic effect where actors play in front of a screen in which a scene is projected from behind, to contextualize and create a dialogue between her works and 1930s cinema. However, when Sherman wishes to discuss the fashion industry, resurrect colors of old masters’ canvases, add fantasy to her American high society portraits, or magnify the assets of clowns, she falls back on chromogenic color prints, a 20th-century technique used to create compelling full-color images. This retrospective isn’t exclusively about period and series; it is also about printing techniques, media, and artistic consistency, and Sherman offers us a glimpse at the evolution of photographic techniques.

Rupture

The Louis Vuitton Foundation unveiled Sherman’s exclusive new series: Men, shown concomitantly earlier this fall at Metro Pictures Gallery in New York. It is the artist’s first series entirely dedicated to masculine characters that marks a substantial step forward. Perhaps she has a statement to make as a masculine character. Perhaps it is a way to think beyond gender, blurring the usual distinctions. The silhouettes—romantically dressed by Stella McCartney in a savory collaboration—rise up above Photoshopped landscape backgrounds, sometimes dreamy, sometimes psychedelic, depending on the characters. For such needs, Sherman uses dye sublimation metal printing, a high definition process known for giving a large color range with great luminescence in order to create contrasts between protagonists and their environments. It is extremely impressive how Sherman knows to play with the medium in order to transmit her intentions in the optimal way, creating resonance between the support and the image.

Her Instagram series announces another breakthrough in her practice, going even further in her search for art, technology, and trends. No more makeup, installation, or implants: The images are made only with the application’s filters to create abominable figures with distorted faces in outrageous colors. She uses the noble and traditional technique of tapestry as a support to the images to accentuate the exaggerated horror of these current-day portraits, reflecting on the contemporary oppression surrounding the idealized canon of beauty in the era of social media. I found this section particularly pertinent today in relation to the global pandemic we have been experiencing. Away from family and friends, our spaces of socialization are de facto limited to phones, internet, and social media. What we were previously using as a hobby, or even as a working tool, has become our almost exclusive means of communication. Likewise, filters, montages, and other modern gadgets have paradoxically come to be the best exoticism we can experience.

Sherman’s Instagram series isn’t only about wildly distorted selfies against kitsch arrangements; it is also about escaping the loneliness and boredom we are all subject to, dreaming of unknown places, funnier experiences, epiphanies. With the confinement and self-isolation we are experiencing all around the world, Sherman’s conceptual portraits turn out to be more realistic than we ever thought.

Whatever she undertakes, Sherman keeps a critical eye on society. Historical references, fashion advertising, cinema, sex pictures, still lives, and so on, are a range of pictorial lexicons proposed and mastered by the artist. She neither falls within the cliché of portrait photography nor into its parody—she is more subtle than that. She questions concept, plays with codes. She does not judge her subjects, treating them with compassion rather than disdain, even if the final results can be cruel. Are her works performances? Contemporary works of art? Photographs? Ego trips? Art market financial investments? The woman of a thousand faces responds to these questions about her oeuvre in the way she knows best: work—for our greatest pleasure.

Cindy Sherman is presented at the Louis Vuitton Foundation in Paris September 23, 2020 – January 3, 2021.

Léa Miranda is a graduate student in law and the history of art at La Sorbonne (Université Paris 1 – Panthéon-Sorbonne). Focusing on the intersections between the two disciplines, her research offers a new approach to the study of cultural heritage, photography, and contemporary art trends.

She has professional experience in museum administration (MAC VAL, Maison Européenne de la Photographie, Paris), and curatorial affairs and production (National Academy of Design, Les Rencontres Internationales de Photographie, Arles), as well as a six-month placement as an intern in the Photographs Department at Christie’s Paris. She is currently a general coordinator at the International College of Photography (CIPGP).

- Calvin Tompkins, “Her Secret Identities,” New Yorker, May 15, 2000: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2000/05/15/her-secret-identities