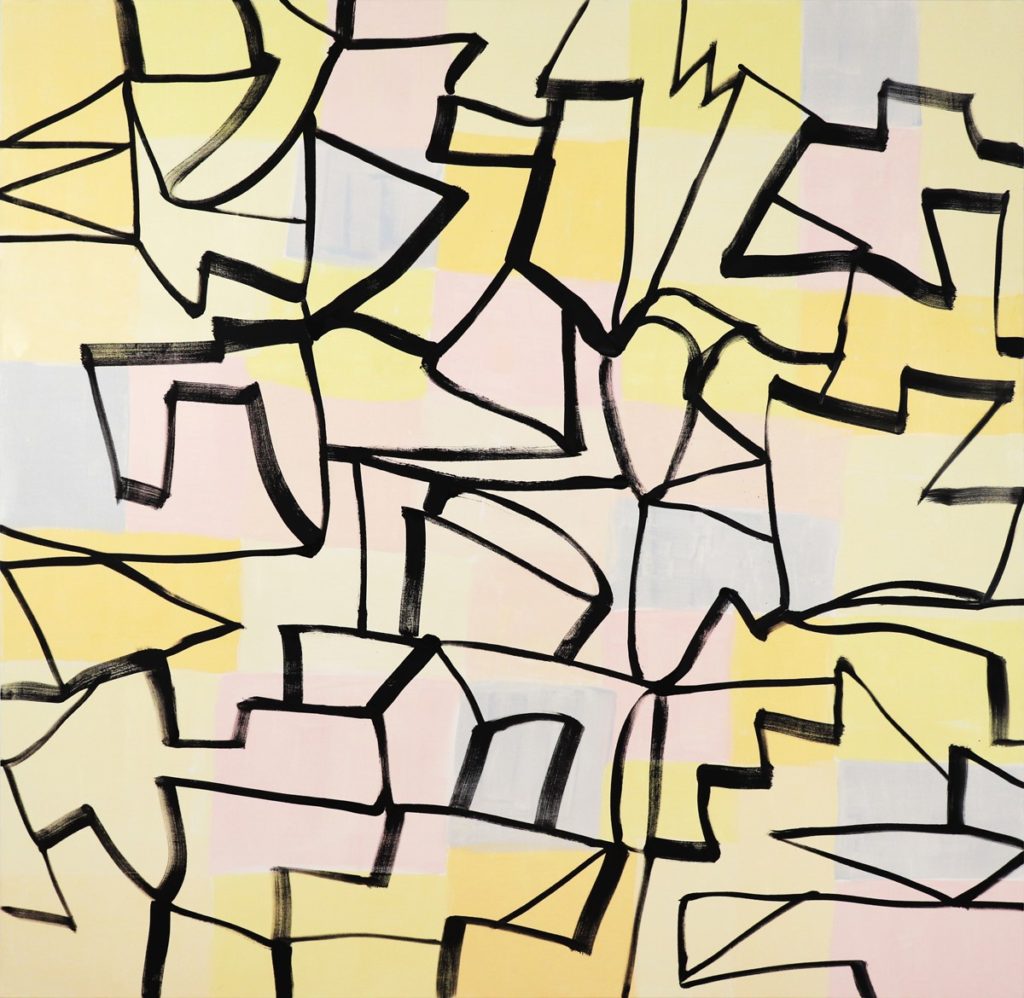

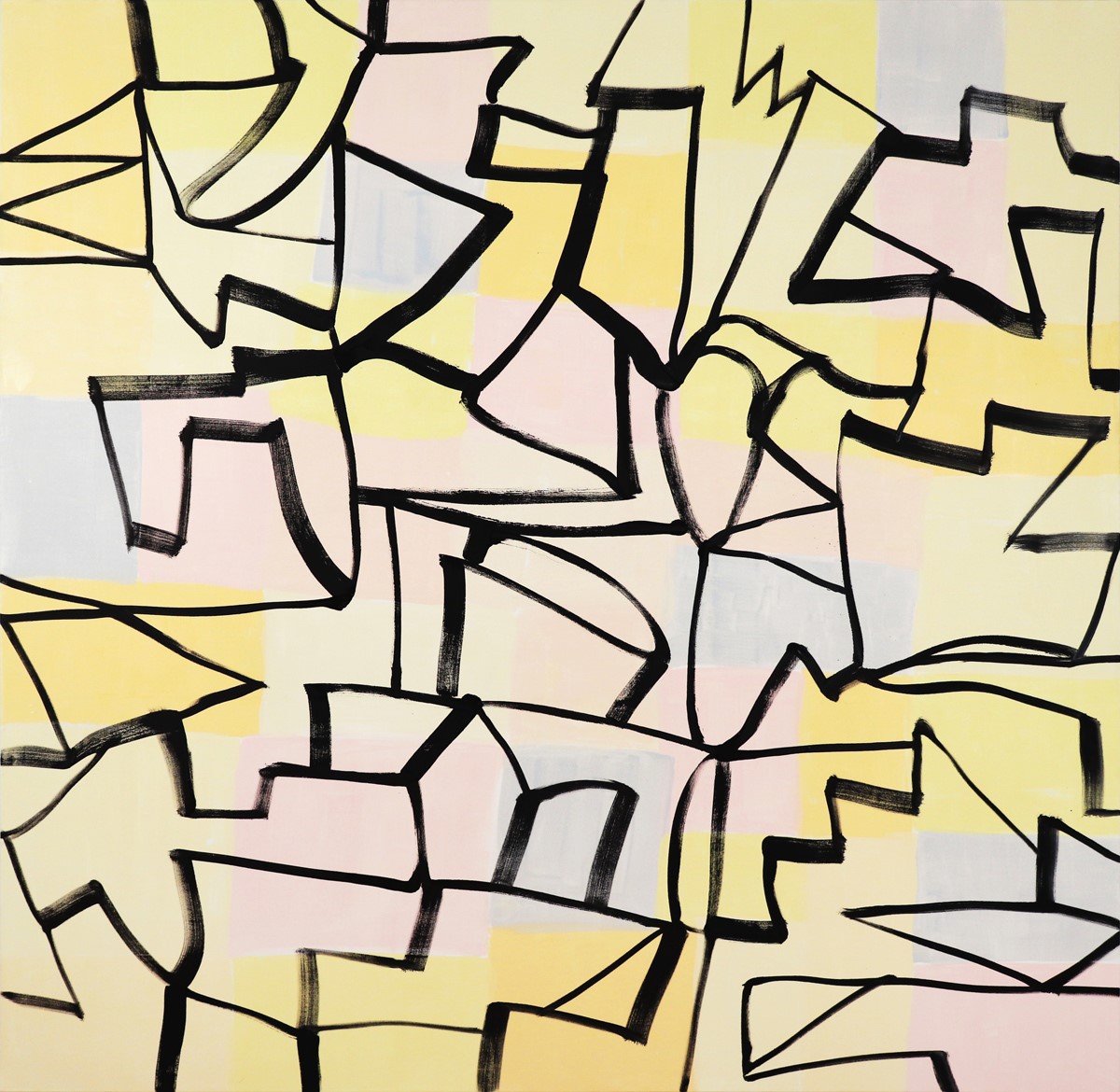

The work of Melissa Meyer (NA 2010) possesses a kind of “sprezzatura”—meaning that it takes a great deal of skill and technical bravado to make it look so easy. Not many artists can pull that off.

By most accounts, Meyer’s work falls squarely within the historical trajectory of Modernism and Abstract Expressionism. One would most likely compare her paintings to the lyrical abstractions of Mark Tobey (ANA 1972) and Bradley Walker Tomlin, and she herself acknowledges their influences, along with the bold gestural works of Lee Krasner. I might also add the later works of Brice Marden (ANA 1992, NA 1994).

But I think Meyer’s visual language is more sly and nuanced than her predecessors’, and most decidedly her own. Her singular contribution to the growing language of gestural abstraction comes from her longtime interest in collage, seamlessly building layer upon layer in her paintings as if she were creating on discreet sheets of glass. The results are remarkable for their luminosity, subtlety of depth, and complexity without ever appearing belabored.

In her current show at Lennon, Weinberg gallery in New York City, up now until December 22, Meyer’s palette, gestures, and titles refer to, among other things, the jazzy cacophony of city life. Many of the paintings in the show are diptychs, and while she has worked in the format before, I was curious about this and her thinking behind the new works.

Leslie Wayne: Tell me about the titles of your paintings here. They are very specific and, in some cases, relate pretty directly to the feeling you get when looking at them like Summer in the City I and II, which are crowded and dense and colorful. Getting in Line made me laugh because it’s exactly how you feel when you’re trying to get onto the L train at Union Square at rush hour! What were you thinking about when you chose these titles?

Melissa Meyer: They’re all pretty direct. J. Mulligan refers to the jazz musician Gerry Mulligan, who I listen to a lot. But I forgot that his name began with a G and not a J, and then it was too late—the piece went out and the title was set! But the work reflects my love of jazz and the kind of syncopated rhythms I try to evoke in my gestures. For Lisa R. is in memory of Lisa Rotell, my beloved yoga teacher who died this past spring. And Iris is for my departed writer friend, Iris Owens, but also refers to the Greek goddess who is associated with communication and sometimes represented as a rainbow. The Summer in the City paintings, besides being made in the summer and nodding to the Lovin’ Spoonful song, were created when I was considering the great Dubuffet show at Pace this past spring, as well as the collages I had made from my cut-out watercolors. I worked hard, labored, suffered, and obsessed about these paintings, and tried not to reveal visually any of this! So I’m glad you mention the term sprezzatura, not least because I first heard it from another dear, departed friend, Stephen Mueller. Finally, Garden in Cassis and Trellis Too are gestures to my residency at the Bau Institute in France in 2016, where I spent a good amount of time in the gardens and by the sea.

A lot of homages to departed friends! I know you were also acquainted with and admired the artist Shirley Jaffe (NA 2012), who lived a long and productive life as an American in Paris. She died in 2016 just three days shy of turning 93. I remember visiting her with you and Svetlana Alpers two years before that, and was impressed by Shirley’s creative output, not to mention her ability to climb those daunting stairs every day at the age of 91! She was a marvelous abstractionist and colorist, and while your works are very different, I do feel there’s a kind of shared spirit between the two of you. She was fiercely independent—like you—and she, too, came out of a tradition of abstract painting with her own unique position. In that way, she was a true feminist; though you’ve said that she would most likely not call herself one. I think of you as a feminist in the sense that you are working within a trajectory of a visual language firmly established by men, but pursuing exactly the line of inquiry that is most personally meaningful to you.

I’m sure I’ve told you about the essay I co-wrote with Miriam Schapiro (NA 1999), “Waste Not Want Not, An Inquiry into What Women Saved and Assembled—FEMMAGE” (first published in the fourth issue of Heresies (PDF) in 1978). Miriam and I brought to light a long and varied tradition of collage used by women way before Picasso and Braque were canonized for their “invention.” I don’t feel I’m a feminist in the typical sense. I simply pursue my own path and fight for my own voice in an arena still dominated largely by men. Though I did join marches in the 60s and 70s and worked on the Heresies Collective’s magazines—organizing and designing.

So interesting. Today, I get the sense that you’re more intent on being taken seriously as an artist—and not a woman artist or a feminist artist. The goal, of course, is to be taken seriously as a great artist, period. But you see, as in the well overdue case of Hilma af Klint, how long that can take! I do think, though, that we’ve made some progress since her time. But let’s move on here. Tell me about your use of the diptych format. I know you have a story about how that first came about.

Yes. Years ago, sculptor Ned Smyth (NA 2016) came over to my studio and put three large paintings together. It had never occurred to me to do that, and it was kind of a revelation—that I could further animate and complicate a work by both combining and dividing up a picture plane. Also, my commission to create the large Shiodome City Center murals in Tokyo made me work in panels that would be viewed from left to right, right to left, and up and down. It really forced me to think about the overall reading of a very, very large surface and how it needs to be organized in sets.

I remember you received another large commission a few years ago, for the American Embassy in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan. That was a large mural project as well, only unlike the Tokyo mural which you painted yourself, this was designed by computer and fabricated in ceramic tile. Did that experience—collaging, in a sense, by computer—inform the way you work today?

I can’t particularly point to how I’m influenced by using the computer—maybe in an unconscious way. I’m still committed to the handmade, and I’m still able to work on paintings on the floor, which I started doing in order to prevent drips, and move around the canvas to “do my dance” (thanks to years of yoga!). I’m still interested and devoted to using a brush! But if I received another commission for an outdoor mural, I would most likely turn to the computer again to construct, or at least complete, the design, which I’d like to see fabricated in glass and or mosaic next time, in addition to the ceramic. The Bishkek project really opened me up to imagining my work in other materials, and that was very exciting. But at heart, I’m still a devoted studio painter.

In the catalogue for your exhibition, there is a wonderful spread of three of your collaged watercolor sketchbooks from 2012 – 2017. I’ve been to your studio and I know how much of your flat files are filled with them! I imagine there is a symbiotic relationship between the sketchbooks and your paintings, though I don’t get the sense that they serve as templates. They really stand alone. Source material for abstraction can be a tricky thing. You want the work to be substantive; to evoke feelings, thoughts, and sensations. But you don’t really want a viewer to look at a painting and go, “aha—now I get it. This comes from that, or this gesture means that.” I know you have a broad and rich array of inspirations, from dance and music, to literature and film. To me, it feels like the shift from the last group of paintings in your show two years ago to this body of work lies more in your personal experience than in outside references or ideas—homages to departed friends, life in the city, time away by the sea. Is that fair to say?

Yes, fair to say. Maybe I’m feeling more sensitive; feeling the loss of recently departed friends, others who are ill, the politics and world turmoil—who knows. Maybe since I just installed this show and am now able to see the work outside of my studio and curated together, it will give me the distance needed to reflect. Perhaps I will be better able to answer that question later on.

I often think about something Willem de Kooning (ANA 1980, NA 1994) once remarked in an interview: “Gorky used to say, ‘very original’ about some of my work, but the way he said it didn’t sound so good… because you have a lot of original art which is not very good art. There’s a difference between being original and being a great artist, or being original and breaking the rules.” I think I’m more interested in being personal and authentic.

New Paintings is presented at Lennon, Weinberg, Inc. from November 1 – December 22, 2018.

New York artist Leslie Wayne (NA 2016) is represented by Jack Shainman Gallery in Chelsea. Wayne is an occasional writer and curator, and has received numerous grants and awards for her painting objects, including a 2017 John Simon Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship and a 2018 New York Foundation for the Arts painting grant.

Melissa Meyer (NA 2010) received undergraduate and graduate degrees from New York University. Her development has been surveyed in traveling exhibitions originating at the New York Studio School and Swarthmore College. She has completed public commissions in New York, Tokyo, Shanghai, and Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan. Her work is in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, the Brooklyn Museum, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, the Jewish Museum, and the McNay Art Museum. Meyer received the Rome Prize from the American Academy in Rome, and grants from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Pollock-Krasner Foundation.