“What is lost when a species, an evolutionary lineage, a way of life, passes from the world? What does this loss mean within the particular multispecies community in which it occurs: a community of humans and nonhumans, of the living and the dead?”

— Thom Van Dooren 1

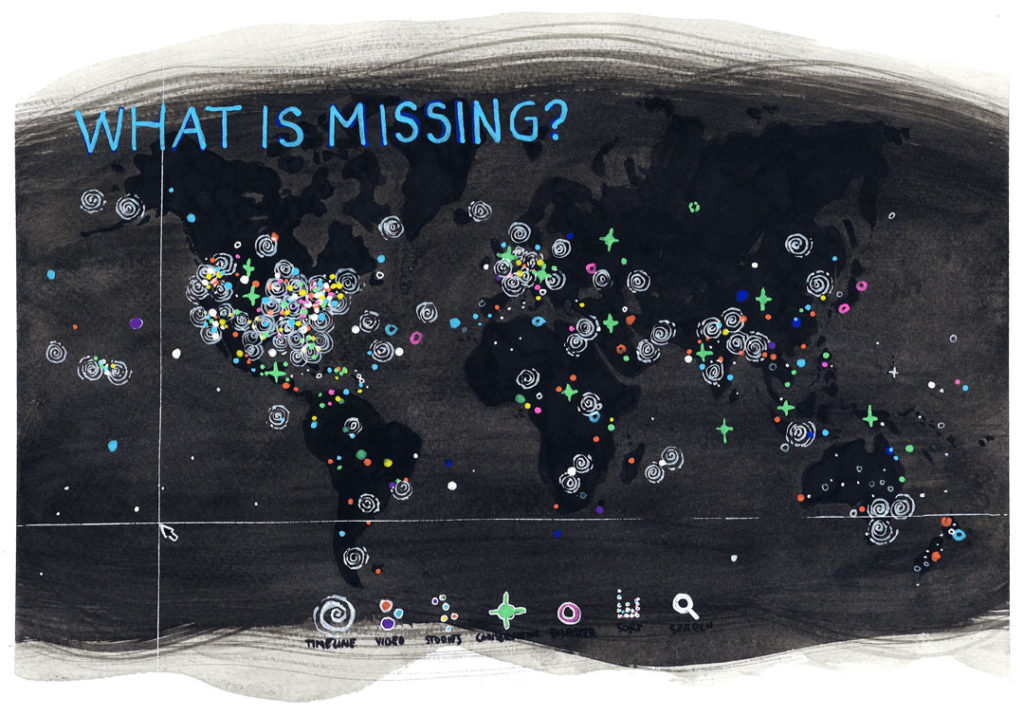

When I first learned that the renowned artist Maya Lin (ANA 1991; NA 1994) designed a digital memorial for endangered and extinct species, I was intrigued. I had visited the Vietnam Veterans Memorial many years ago, and I felt deeply moved by the power of her design to evoke memory and emotion. How would she pivot from memorializing humans to more-than-human species? What memories and emotions would it stir within me? Why did she title the project What Is Missing?

The first thing I notice on the What is Missing? website is that the map splits the Pacific Ocean in two halves. I look to the right margin for my ancestral home island of Guam, which is a territory of the United States. There are overlapping bright, pulsing icons in the watery space where I know it should be. I move the cursor over it and multiple texts and images pop up. I already know what this signifies: There are many species missing from Guam. Even though the tiny island only comprises approximately 210 square miles, it is considered one of the “extinction capitals of the world.”

I search for Guam and there are six results: “Invasive Species, Brown Tree Snake (1960),” “Guam Flying Fox (1974),” “Imported Brown Tree Snake Decimates Native Species (1980),” “Extinct in the Wild, Micronesian Kingfisher (1986),” “Extinct in the Wild, Guam Rail (1987),” and “Guam Under Siege From Pollution and Development (1995).” A pencil icon on the bottom of each entry prompts: “Add a Memory.” Not a single memory has been added to Guam.

~

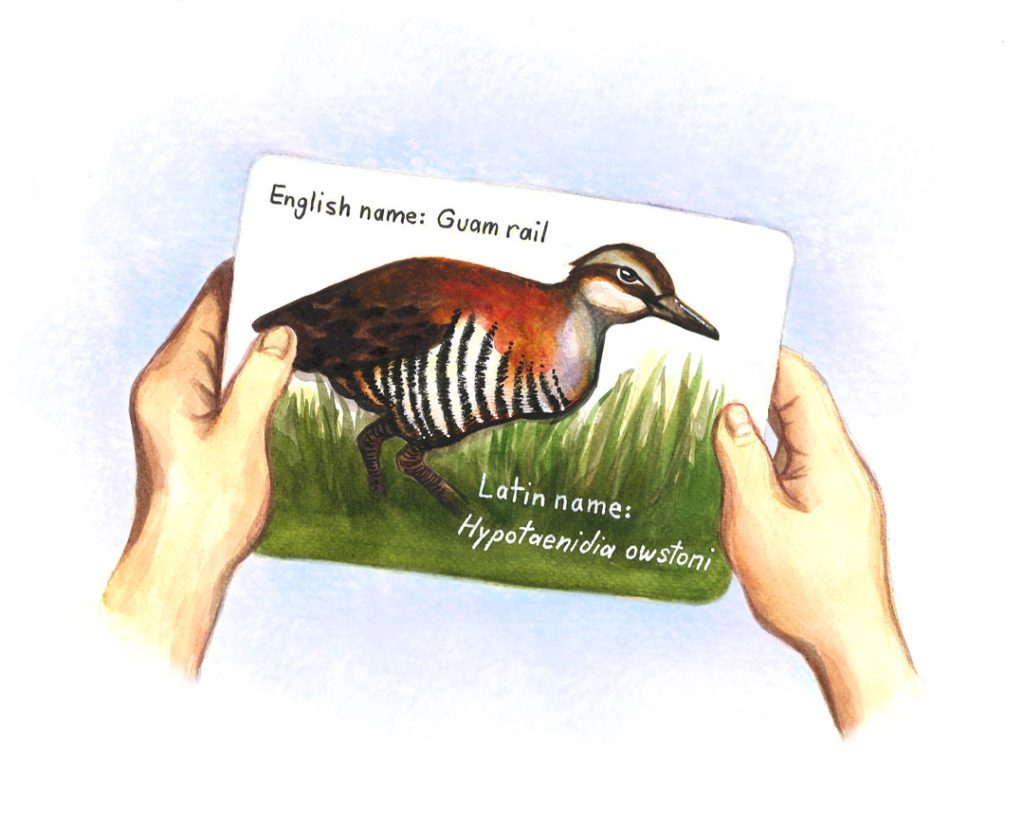

I remember sitting in my 4th grade classroom at Carbullido Elementary School, located in the central village of Barrigada, circa 1990. Our teacher handed out flashcards of “The Native Birds of Guam.”

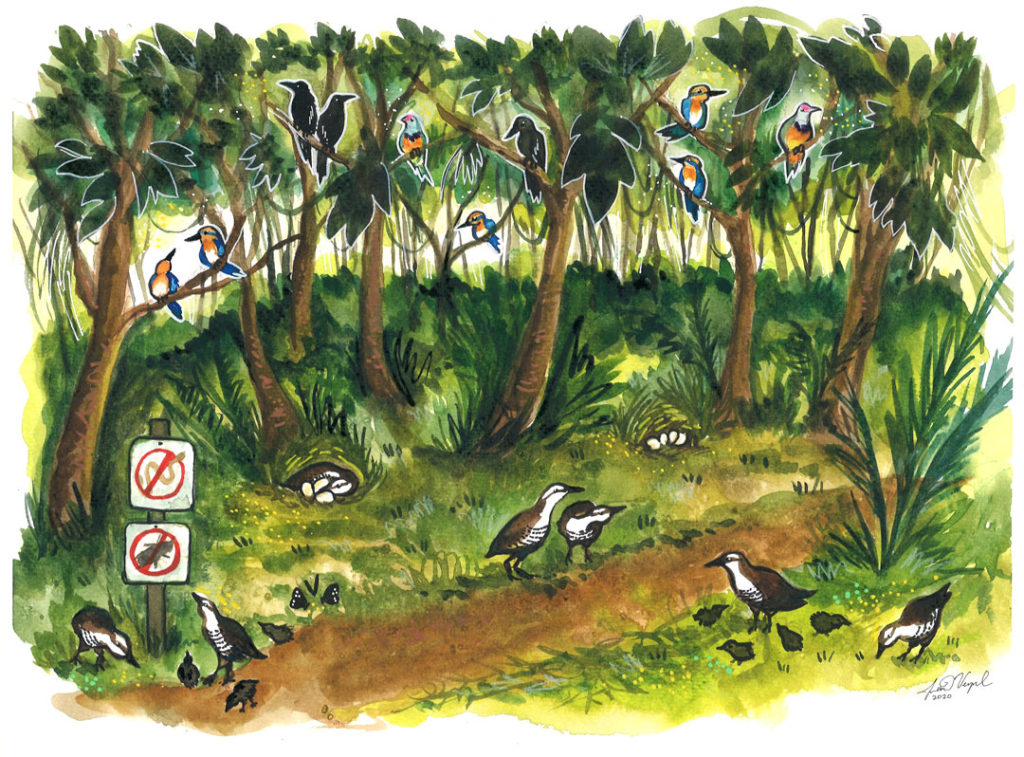

Our school is the “Home of the Ko’ko’s.” The ko’ko’ is the CHamoru name for an endemic, flightless yet fast-running bird. I study the flashcard: English name: Guam rail. Latin name: Hypotaenidia owstoni. Chocolate-brown heads and necks, a gray stripe just above the eye, gray breast with white stripes, dark wings with brown spots and white bars.

Even though this bird was our mascot, I have no memories of ever seeing a ko’ko’ in real life because it was already extinct in the wild.

The next day, our teacher gave us a blank piece of paper and we had to draw and color the ko’ko’ from memory.

~

Our next assignment: Create a timeline of the arrival and spread of the brown tree snake (Boiga irregularis) on Guam. They came as stowaways aboard US military supply ships after World War II and colonized the entire island since they had no natural predators. Their population: two million. Density: 12,000 snakes per square mile. Guam is one of the most snake-infested places in the world.

One night, a snake crawled through a torn window screen into my parents’ bedroom. My mom screamed. My dad grabbed the machete he kept under the bed. I still remember the snake cut in two—streaks of blood. On the news, every “brownout” was caused by snakes biting through electrical wires or slithering into generators. At school, the kids told rumors of snakes crawling into cribs and killing babies.

In class, the words “endangered,” “endemic,” “extinction,” and “extirpate” were on our vocabulary list.

~

Conservationists from the United States arrived to study the problem in the 1970s. When they realized that the snakes were causing the bird population to decline, it was too late: Ten of the twelve native bird species already vanished from the wild. So they tried to save as many as possible. In 1987, they captured 21 of the last wild ko’ko’ (and a few eggs) and shipped them to zoos for captive breeding programs.

Our teacher played a cassette tape recording of the ko’ko’ birdsong, which I had never heard in real life. Kee-yu kee-yu kip kip kip. We mimicked the birdsong aloud as a class. The jungles of Guam, once fertile with birdsong, had grown silent.

~

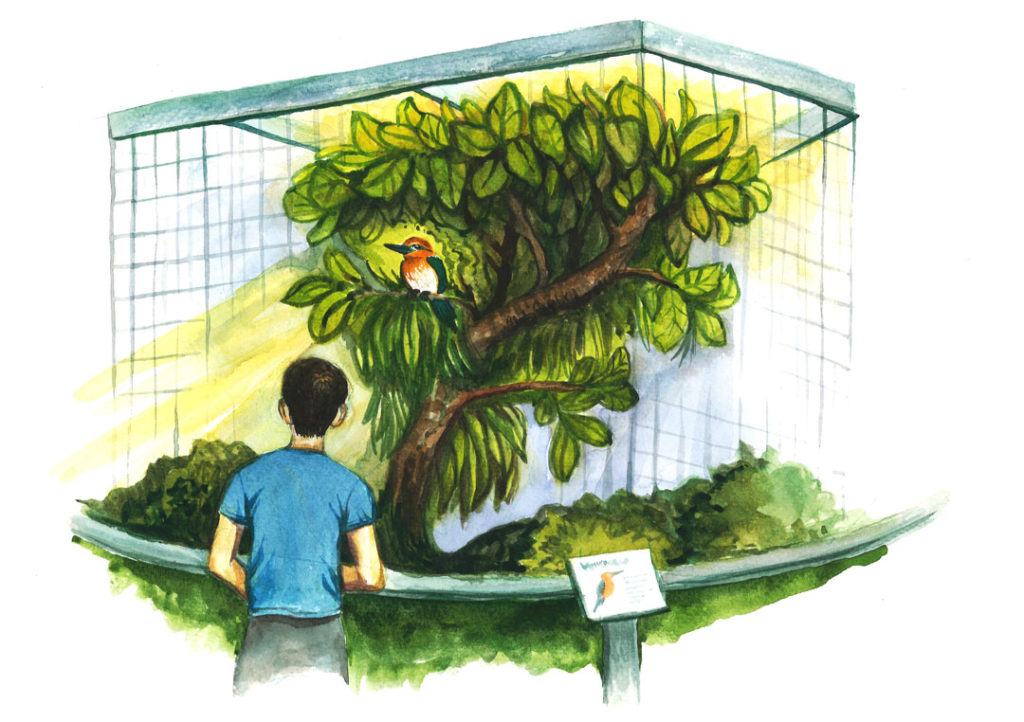

Even though the ko’ko’ was our school’s mascot, my favorite bird was the sihek, or Micronesian kingfisher, because they are so colorful. Blue tails, metallic green-blue wings, orange, cinnamon, and white breasts. Long black beaks.

In 1984, conservationists captured 29 wild sihek on Guam for captive breeding programs. The last wild sihek was seen in 1988. Kshh-skshh-skshh-kroo-ee, kroo-ee, kroo-ee.

“The zoos are taking care of the birds, keeping them safe,” our teacher said. “Maybe someday, Guam will be safe enough for them to return.”

I received an “A” on the unit, but I felt so sad.

~

In 1995, when I was 15 years old, my family migrated to California, which is a 14hour flight from Guam. CHamoru people—like many other Pacific Islanders—migrate for a number of reasons, including economic and educational opportunities, health care services, and military service. By 1980, 30,000 CHamorus lived in the states; by 1990, that number grew to 50,000; by 2000, the population nearly doubled to 92,000. As of 2010, an estimated 150,000 of us have settled in all 50 states and even Puerto Rico. California is home to our largest diasporic population, numbering around 45,000, with the highest concentration in the city of San Diego.

Today, more CHamorus live in the diaspora than back home on Guam.

My people started migrating in large numbers around the same time our native birds began disappearing.

~

I graduated high school and attended a university in Southern California. During orientation week, a student group sponsored a visit to the San Diego Zoo. I joined the excursion to make new friends, so I was not prepared for what I encountered that day.

When we entered the bird section, I saw, in a large cage, perched on a branch, for the first time in my life: a living sihek.

For a moment, I questioned whether what I saw was real or if it was a ghost. I looked at the placard on the front of the cage: “Micronesian kingfisher (Todiramphus cinnamominus). The rarest species in San Diego Zoo Global’s avian collection.”

“Hafa adai,” I whispered, our traditional CHamoru greeting. While the other students must have thought I was strange, I couldn’t help but talk to the bird, share my name, my clan name, my village. “Guahu si Craig Santos Perez, familian Gollo, ginen Mongmong. But I live in California now, just like you.”

~

Sadly, every effort to eradicate the brown tree snake on Guam has failed. Innovative snake traps, trained snake-sniffing dogs, snake hunting competitions, and even the infamous “mice drop.”

In 2013, scientists laced dead baby mice with acetaminophen (toxic to snakes), attached cardboard parachutes to their bodies, and dropped them from helicopters into the jungle. Thousands of mice fell from the sky and hung from tree canopies as bait. This multimillion-dollar experiment also failed. Guam has become a scientific laboratory to study the impacts of invasive species and test strategies to control them.

Since Guam’s birds disappeared, the jungles are not only silent, but they are also now filled with spiders that the birds used to eat. Moreover, the jungles are starting to thin since most tree species rely on birds to disperse and germinate seeds. Guam has more spiders than other nearby islands and new growth of the island’s trees have fallen by as much as 90%. The loss of our birds continues to echo throughout the fragile, tropical ecosystem.

~

There are only around 150 sihek alive today at more than two dozen zoos across the United States and at one government facility on Guam. The sihek have had difficulty breeding and rearing chicks in captivity, and the population is too small and vulnerable to be released in the wild.

The ko’ko’ breeding program has been much more successful. So much so that by 1998, between 50 – 100 birds were being introduced to a “replacement habitat” each year in the snake-free island of Rota, north of Guam. In 2010, a number of ko’ko’ were released on Cocos island, a snake-free islet off the southern coast of Guam. Today, Rota is home to around 200 ko’ko’ and another 60 – 80 live on Cocos. There has even been evidence of natural breeding and chick rearing.

In 2019, the ko’ko’ became only the second bird in history to recover from being declared “Extinct in the Wild” (the first was the California Condor) by the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List. Despite this historic and hopeful news, the ko’ko’ is still classified as “Critically Endangered,” since the Cocos island population is still vulnerably small and the Rota population still requires active management before the birds are considered fully self-sustaining.

Maybe someday Guam will be safe enough for our birds to return home and rewild the jungle with birdsong.

~

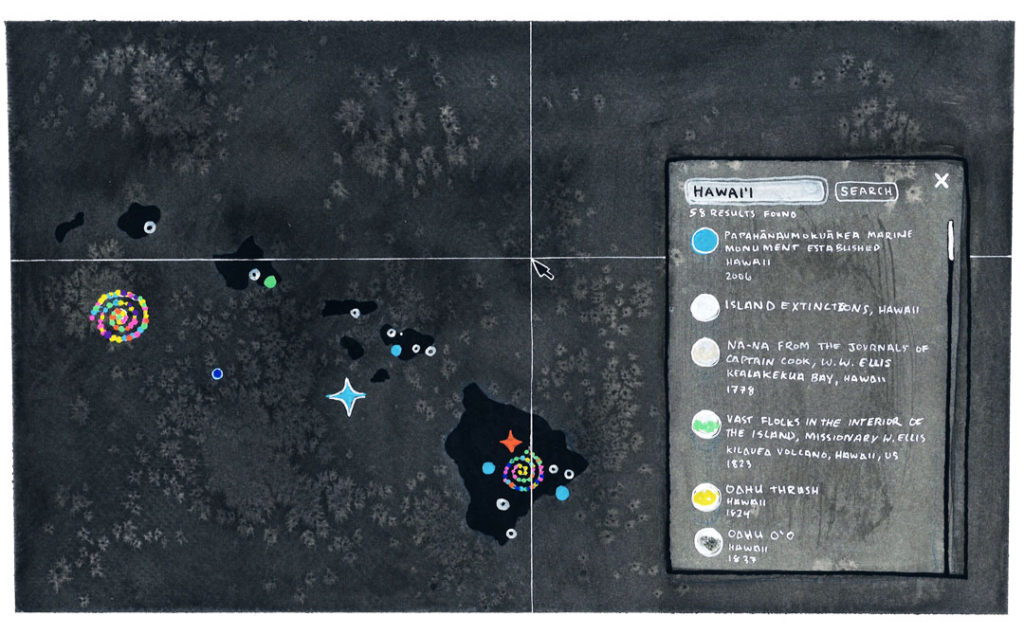

In 2010, I moved to Hawaiʻi, which is also considered one of the “extinction capitals of the world.” I return to the What is Missing? map and see that Hawaiʻi is on the left margin of the halved Pacific Ocean. Like Guam, there are many overlapping icons crowding the Hawaiian Islands. I search Hawaiʻi: there are nearly 60 entries, including many entries related to birds. While the brown tree snakes have not invaded Hawaiʻi, other factors have endangered the birds, including deforestation, militarization, and urban development.

My wife, who’s Native Hawaiian, has told me many stories about the birds here. One I was particularly drawn to was the Kauaiʻi ʻōʻō, a species of honeyeater. What is Missing? contains an entry on this bird with a quote from The Condor’s Shadow: the Loss and Recovery of Wildlife in America by David Samuel Wilcove:

“The most poignant loss, however, may have been the Kauaʻi ʻōʻō. A sleek chocolate-brown bird with bright yellow thighs, it was the last of a noble line of ʻōʻō that were celebrated in Hawaiian folklore for their beautiful feathers. The ʻōʻō that once lived on Oʻahu, the Big Island, and Molokaʻi had been driven to extinction by the beginning of the 20th-century, leaving the Kauaʻi species as the sole survivor. A small population held out in the heart of the Alakaʻi wilderness, delighting the handful of intrepid ornithologists who sought them out. About 36 birds were thought to survive in the early 1970s. Within a decade, that number had dropped to only two, a pair nesting in the big ʻōhiʻa tree. After a hurricane struck Kauaʻi in 1982, only one individual, a male, could be located. He survived for four more years, vigilantly guarding his little territory, constantly singing for a mate that never appeared.”7

Learning about the different histories and fates of the ko’ko’, sihek, and ʻōʻō fills me with grief. My heart, like the Pacific Ocean, splits in two. Our native birds not only brought beauty and music to our islands, they also carried on their wings a responsibility to the overall health and harmony of tropical ecosystems. The disappearance of native birds has taught us the dangers and impacts of invasive species and environmentally destructive practices.

As Thom Van Dooren highlights in the epigraph, when we lose a species, the depth of the loss is trenchant and unfathomable. More than just their physical presence is lost. We lose an entire part of our kinship network, our more-than-human family. We lose part of our culture and the symbolic meanings that birds teach us about living in this world. I look over the entire map of What is Missing?. So much loss, everywhere. Is it safe, anywhere? The scale of the sixth mass extinction is disorienting, engulfing.

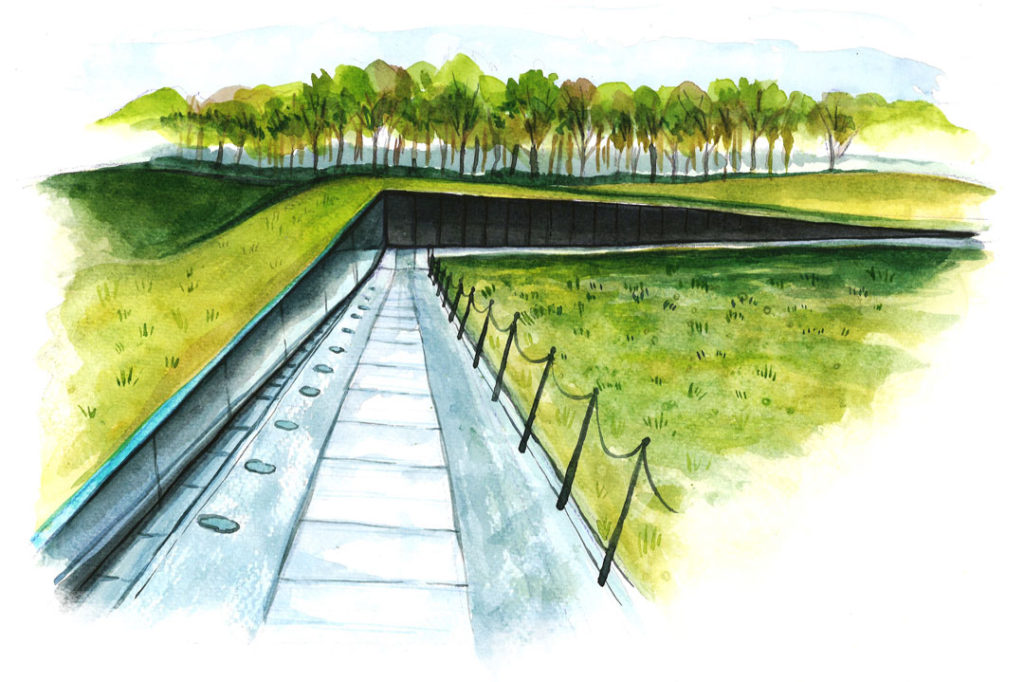

The black and gray interactive digital map of What is Missing? reminds me of the black granite stone of Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial, which I visited many years ago because my dad is an Army vet who was drafted during the Vietnam War. He survived, unlike many other CHamorus whose names are inscribed on the wall. So much loss, so many names to remember.

What is Missing? is a profound and dynamic “global memorial to the planet.” For me, it has created a space to feel my grief, reflect on extinction, and remember what was lost. It has inspired me to do what I can to conserve what has survived, restore our relationship to the world, and cultivate hope for a more sustainable future. Thank you, Maya Lin and everyone involved, for creating this space for us.

To conclude, I want to share one of my poems, “The Last Safe Habitat,” which was written after I read, with my five-year old daughter, a book about the native birds of Hawaiʻi. The poem appears in my book, Habitat Threshold:

The Last Safe Habitat

I don’t want our daughter to know

that Hawaiʻi is the bird extinction capital

of the world. I don’t want her to walk

around the island feeling haunted

by tree roots buried under concrete.

I don’t want her to fear the invasive

predators who slither, pounce,

bite, swallow, disease, and multiply.

I don’t want her to see the paintings

and photographs of birds she’ll never

witness in the wild. I don’t want her to

imagine their bones in dark museum

drawers. I don’t want her to hear

birdsong recordings on the internet.

I don’t want her to memorize and recite

the names of 77 lost species and subspecies.

I don’t want her to draw a timeline

with the years each was ‘first collected’

and ‘last sighted’. I don’t want her to learn

about the ʻŌʻō, who was observed atop

a flowering ‘Ōhiʻa tree, calling for a mate,

day after day, season after season.

He didn’t know he was the last of his kind,

or maybe he did, and that’s why, one day,

he disappeared, forever, into a nest

of avian silence. I don’t want our daughter

to calculate how many miles of fencing

is needed to protect the endangered birds

that remain. I don’t want her to realize

the most serious causes of extinction

can’t be fenced out. I want to convince

her that extinction is not the end. I want

to convince her that extinction is just

a migration to the last safe habitat

on earth. I want to convince her

that our winged relatives have arrived

safely to their destination: a wondrous

island with a climate we can never

change, and a rainforest fertile

with seeds and song.10

Dr. Craig Santos Perez is an indigenous CHamoru writer from the Pacific Island of Guåhan (Guam). He is the author of five books of poetry and the co-editor of five anthologies. He is a professor of English at the University of Hawaiʻi, Mānoa.

Born and raised in Seattle, Washington, Jessica Vergel is pursuing her BFA in Packaging Design at the Fashion Institute of Technology. Through painting and mixed media work, Jessica continues to explore her CHamoru and Filipino ancestry. Recent creative endeavors include showcasing garments with Guma’ Ge’la at London Pacific Fashion Week in 2019, and painting a mural in the USDA Plant Inspection Station at the Honolulu International Airport.

- Thom Van Dooren, Flight Ways: Life and Loss at the Edge of Extinction, 2014. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Illustration references: Maya Lin, What Is Missing?, 2010, and Graphics Factory CC, Vector World Map, 2009.

- Illustration reference: Greg Hume, “Guam Rail at the Cincinnati Zoo,” Wikimedia Commons, 2011.

- Illustration reference: Ryan Somma, “Todirhamphus cinnamominus,” Wikimedia Commons, 1980.

- Illustration reference: User geomorph, “Lost Forest – Birds of Australasia – Micronesian Kingfisher Exhibit,” Zoo Chat, 2014.

- Illustration reference: Maya Lin, What Is Missing?, 2010.

- David Samuel Wilcox, The Condor’s Shadow: the Loss and Recovery of Wildlife in America, 1999. New York: W.H. Freeman and Co.

- Illustration reference: Huub Veldhuijzen van Zanten and Naturalis Biodiversity Center, “Moho Braccatus (Cassin, 1858),” Wikimedia Commons, 2005.

- Illustration reference: Chris Phan, “Vietnam Veterans Memorial,” Flickr, 2009.

- Craig Santos Perez, Habitat Threshold, 2020. Richmond, California: Omnidawn Publishing.