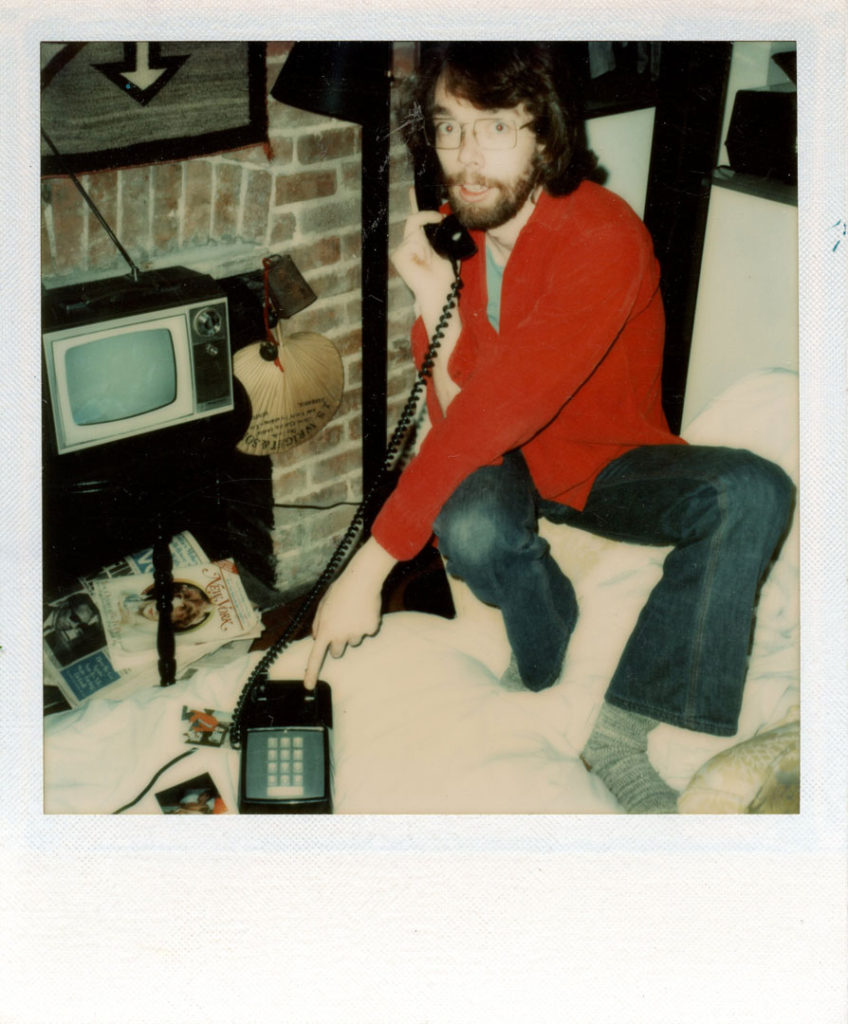

Jimmy Wright (NA 2018) is an artist currently based in New York City’s Bowery district. Born in Union City, Tennessee, and raised in rural Kentucky, Wright settled in New York in 1974. During his early years living in the city, Wright’s work provided a kaleidoscopic document of the city’s still burgeoning queer spaces—Meatpacking District bars like the Anvil as well as the gay bathhouses spread throughout Manhattan. His paintings and drawings from this era—vibrant, figurative, deeply saturated—provide a glimpse of the communal, complicated, and jubilant nature of gay life in the city just before the devastation of the AIDS crisis. One of these early works is included in Around Day’s End: Downtown New York, 1970–1986, which runs through October 25 at the Whitney Museum. Curated by Laura Phipps and Christie Mitchell, the show contains a selection of works from the museum’s collection that explores Downtown New York as site, history, and memory, and is a sort of preamble to the completion of David Hammons’s Day’s End, a major public artwork that will be located in Hudson River Park. In addition to Wright, the show also features a number of other National Academicians: Dawoud Bey (NA 2015), Christo (NA 2011), Robert Morris (NA 2016), Joan Jonas (NA 2012), Richard Serra (NA 2016), and Kiki Smith (NA 2016). I spoke with Wright about his work, the value of queer spaces, and what it means to be an artist living and working in New York City at the height of a global pandemic.

T. Cole Rachel: How does it feel to be in New York City right now?

Jimmy Wright: I’m good. I’m healthy. But, as I’m sure you understand, no matter how good you feel, there is an undercurrent of anxiety over the world that we’re living in. Politically and health-wise. It unfortunately reconnects me to the AIDS crisis. I’m sure that’s true for a lot of men who are survivors of that period. Today’s challenges are completely different, but anxiety is anxiety.

I’ve lived on the Bowery since 1976. I moved to New York in 1974 and first lived in Boerum Hill, Brooklyn, across the street from Jean-Michel Basquiat, who was then a teenager. Now, I live right off the Bowery, and I’m seeing a different kind of presence among the homeless that I haven’t seen before. A lot of it is mental illness. I’m seeing guys that are in their early 30s. When I moved here years ago, the building next door was a Salvation Army shelter. I moved onto a burnt-out block that was a center for heroin sales, which was the reason I could buy this little building that was originally used as a stable. Much later, after the neighborhood transformed, a developer bought that building next door and added floors, and it turned into an Ace Hotel franchise and a hipster destination. He now has a contract with the Bowery Residents’ Committee, which works entirely with the homeless. So, it’s back to being a shelter for the homeless. There’s such a rich irony in that.

When I moved here in the ’70s, New York was in the throes of a financial crisis and all of the Lower East Side was burnt out. But I was 29 years old and fearless. Now, as a 76-year-old, I have to watch that I don’t go to a dark place. To go back to the AIDS crisis, it was the same then. I was taking care of someone, and I had to watch that I kept my focus on his care and both of our health and not tumble into a trap door of despair.

Your early work documented a part of New York City that sadly no longer exists. It’s interesting to be looking at that work right now—all these representations of queer spaces—at a time when no one can be in shared spaces. It feels even more poignant.

This is all compounded for me because I’m now 76. In the ’80s, many of those spaces closed, and much of the community died. Those spaces that I experienced when I was 29 or 30—even if they existed now—wouldn’t necessarily be spaces where I would be comfortable or accepted in the way I was when I was younger. So, you add age to that, and it makes it seem like a long time ago.

There is so much interest now regarding the culture of Downtown New York in the ’70s. Is it weird to constantly be asked to talk about this period and to interact with your work that documents this time?

On an art level, no, because it’s part of my body of work. The kind of games I played stylistically with that series was something no one at the time understood. And, so, it’s gratifying to know that it’s been embraced by so many serious artists and collectors. I also find it fascinating that this much younger generation has given me a vocabulary. When I went off to art school in the fall of 1963, “gay” was not even in my vocabulary. All the negative terms were, but there were no positive terms. I was coming from a farm in Western Kentucky. I had no clue. Being introduced to Southern writers was such a revelation because it gave me a narrative. It showed me how I had my own personal narrative, not only for who I was but for who my family was, how they behaved, and why they behaved like that. In 1969, experiencing gay liberation was also a revelation for me; it gave me an armor to confront the world with. That was where a lot of my work was coming from at that time. I look at the younger generation now, so at ease with their bodies, at ease with their identification, and their fearlessness with political action. It’s invigorating.

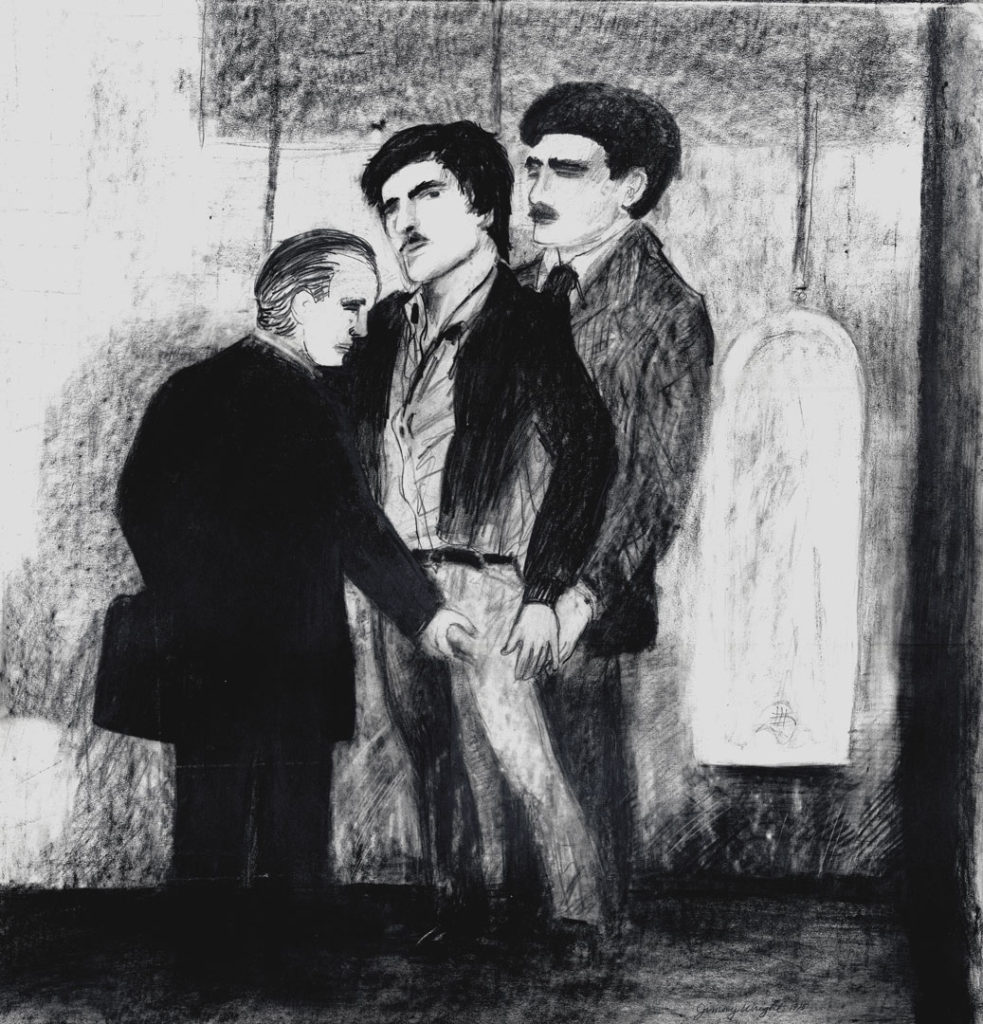

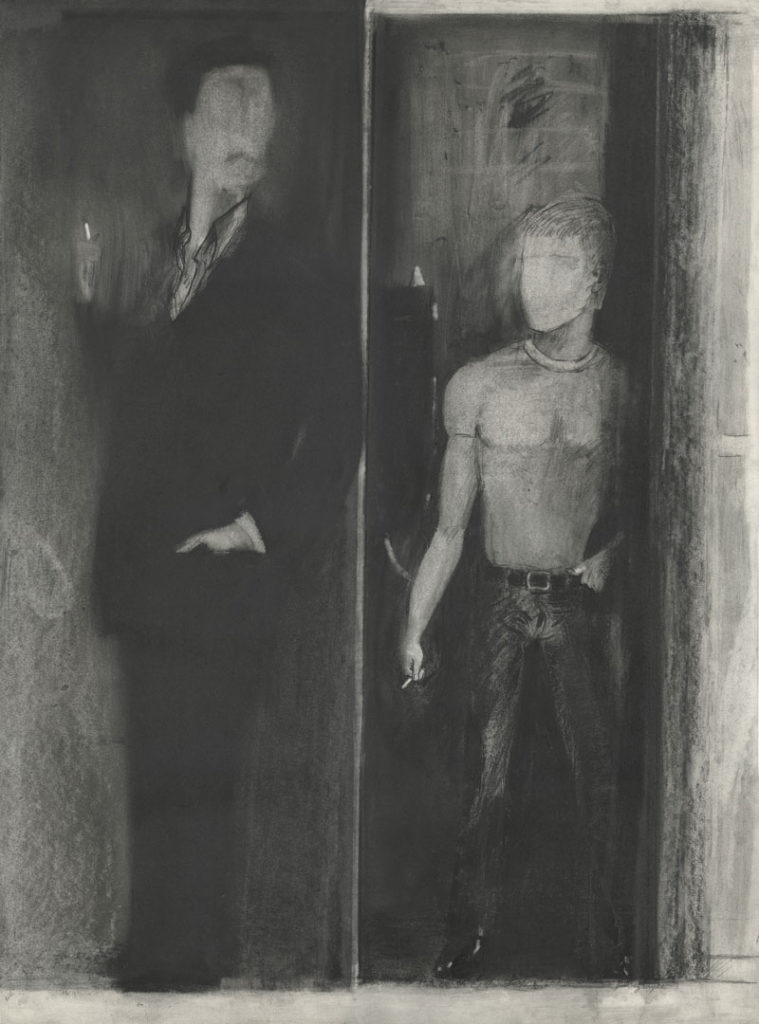

The piece you have in the Whitney show, Anvil #1, 1975, is this beautiful depiction of a night at the Anvil nightclub, complete with a fisting show and a prominently displayed can of Crisco. When you were making this image and the bathhouse images, how did you tend to work? Would you just go home and immediately start sketching what you had seen, or did you make references?

It was all from my head. It was about absorbing the scene and then working later. And not even necessarily the next day. It might be three weeks from then when I didn’t have $10 to go to the Club Baths, so I stayed home and painted instead. That was a period of extreme hand-to-mouth existence, of figuring out how I was going to pay the rent and survive in New York City. There were no sketches on-site or anything. I was just absorbing things visually. The first two years of my art education was drawing the figure almost every day, so that was my foundation. My most influential instructor was Ray Yoshida. His approach involved an immersion in a narrative that’s not tied to realism but instead is tied to formal approaches to the picture plane. But those formal approaches could be taken from naïve art, or from Cubism, or from pattern-based designs. I was introduced to looking at all kinds of rich sources that continued to inform how I approached something visually. I was so inspired by what I saw on the streets of New York. So, when I walked into a club where there was something being used as a makeshift stage, two guys were using double dildos on each other, and et cetera—it just added to that vocabulary. This was something I was going to go home and draw.

Why is it important to remember and celebrate these kinds of queer spaces that no longer exist? What makes them so interesting?

All of these spaces were marginal. They were invisible to the rest of the culture. It was mind-blowing for me to walk out in the street and suddenly be engaged in a cruising episode on a subway platform amidst other people in the wide open. You think it would be obvious, but people were oblivious. Or to wander into a park and find it alive with outlaw sexual activity. Or to follow someone into the restroom at the Museum of Modern Art for a hookup.

It was so clandestine—so much of gay life at that time—but at the same time it was incredibly open and I never understood how it was so open to me and yet so invisible to others. So, yes, there was a kind of physical freedom, but it was always pushed to spaces that were abandoned and physically dangerous. People romanticize it, but it was actually very dangerous.

And I’m not sure a younger generation has experienced that or needs to experience that. That’s one big change with smartphones and apps and social media. You and I are talking to each other via video from our homes. We could have hooked up on Grindr and now be communicating from our homes. You’re not in a loading dock in the West Village, walking into a pitch-black open trailer truck where you have no idea who’s inside or what’s going to happen. There was the thrill of the danger involved, but now you don’t have to do that in order to connect with other gay people or to find sex.

People now really adore this body of work—these drawings of bathhouses and sex clubs and the illustrations you made at Max’s Kansas City—but how did people feel about it at the time?

There was no interest in it. There’s an irony for me that I’m now in this show with very conceptualized, site-specific artists and that this body of work from the ’70s can now also be looked at in that context. It’s interesting to me that this work plays a lot of formal, different roles that, at the time, I didn’t see. I was just aware that I was in a city where the gay community was exerting itself in a very aggressive, visual way. It was exhilarating to participate in it.

In 1967, I graduated from the Art Institute of Chicago and won a travel fellowship, which I used to go to India. On the way, I left for London from New York—this was 1968—and the one gay man I knew in New York took me to Stonewall to dance. Eventually, I ended up in graduate school at Southern Illinois University. I drove cross country to visit friends in San Francisco, and the first night there, I went to a gay lib dance at UC Berkeley. And, of course, I immediately met someone and spent two weeks with him. I came back to Southern Illinois with this fire to do something. I knew we needed a gay organization on campus like they had in Berkeley.

I was one of three that started the gay lib group on campus, and we didn’t have a clue what we were doing. We just knew we needed to exist and to signal to other gay men and women that we were there. And, so, these drawings, in a sense, were a continuation of that need. I had had a close gay friend murdered in Chicago. I had had a high school boyfriend come home from grad school and commit suicide. I wanted things to change. It was that sense of, “What have I got to lose? I’m queer, I’m here, get over it.”

Around Day’s End: Downtown New York, 1970–1986 is presented September 3 – October 25 at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

T. Cole Rachel is a writer, editor, and teacher who lives in Brooklyn.

Jimmy Wright (NA 2018) is an artist currently based in New York’s Bowery district. Born in Union City, Tennessee, and raised in rural Kentucky, he studied at Murray State University in Kentucky, and attended the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in the early 1960s, earning his BFA in 1967. He finished graduate school at Southern Illinois University in Carbondale in 1971. In 1974, Wright settled in New York City. His work has been shown at the Art Institute of Chicago; the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; and the Museum of Modern Art, New York; and he is represented by FIERMAN (New York) and Corbett vs. Dempsey (Chicago).