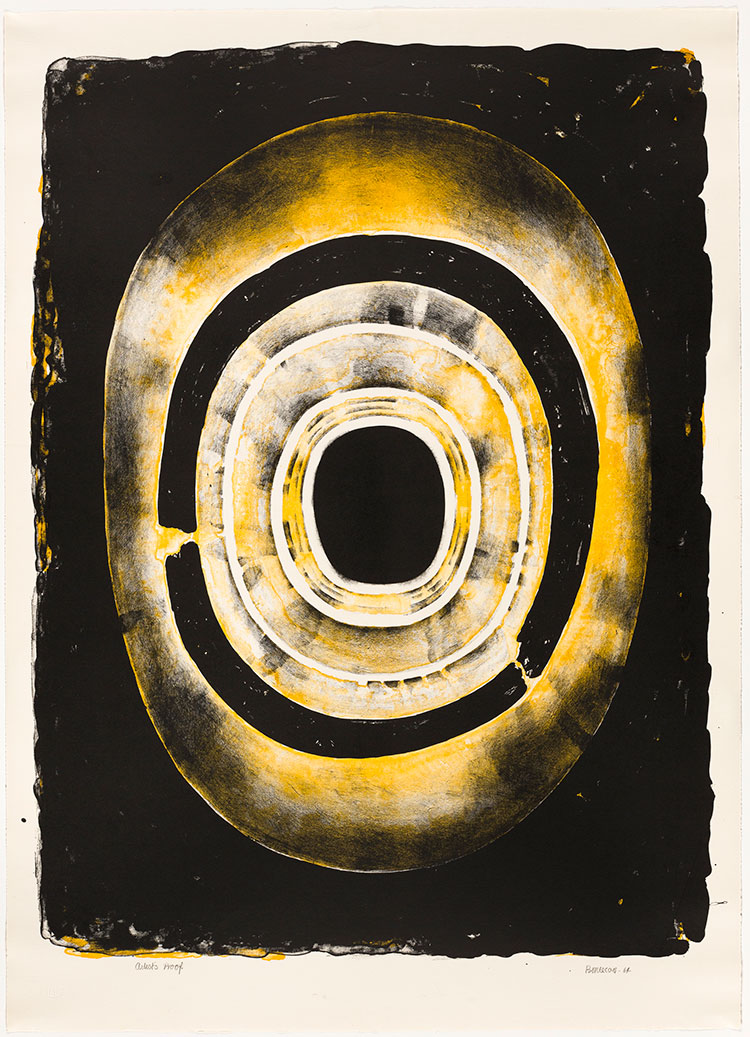

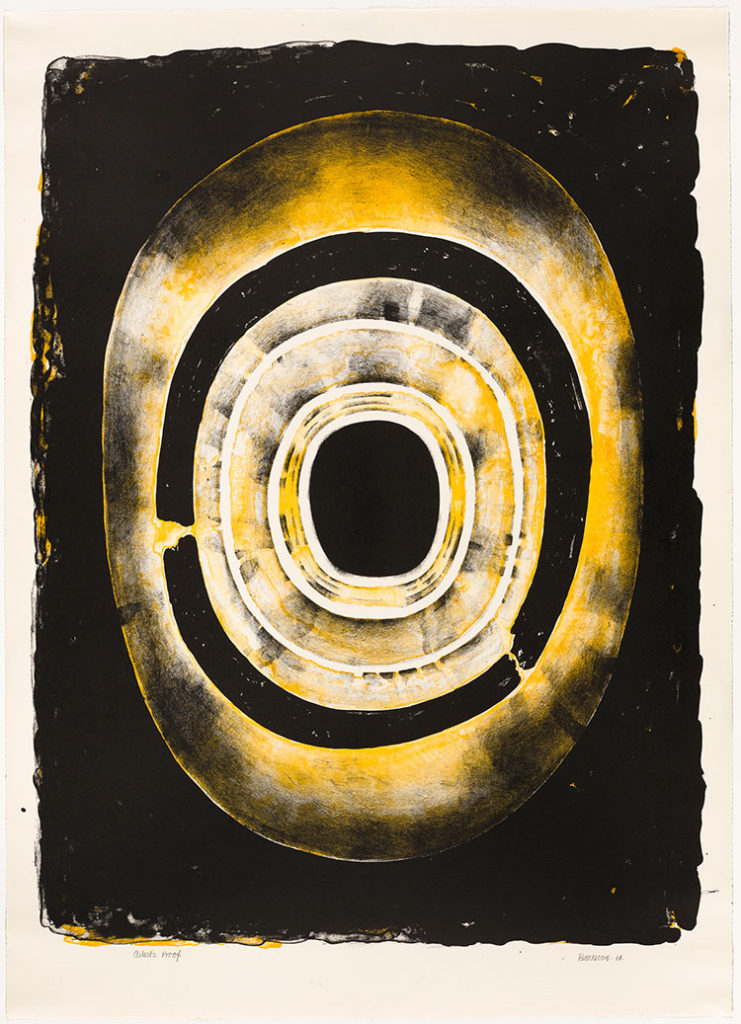

Voids, black holes, and cavernous openings show up frequently in the work of Lee Bontecou (NA 2004), born 1931. She is best known for creating mesmerizing wall reliefs. Her prints are similarly captivating, if perhaps less often cited. Into the Void: Prints of Lee Bontecou—which runs through May 5 at the Art Institute of Chicago—is the first show devoted to Bontecou’s prints since 1975. It includes over 100 objects, such as preparatory drawings, working proofs, and the copper etching plates used to make Bontecou’s works.

The prints were produced between 1962 and 1982 at Universal Limited Art Editions (ULAE), a workshop in Islip, New York, founded by printmaker Tatyana Grosman. It was the Cold War era—a time when Americans, the artist included, were thinking about the wonders and mysteries of space travel and the threat of nuclear attack.

Into the Void is anchored by one of Bontecou’s wall reliefs (Untitled, 1960, steel, canvas, and copper wire construction). The piece is prominently featured at the entrance to the exhibit. The motif of the black void is present in both the wall relief and the framed prints surrounding it. Some of these (like Sixth Stone I, II, and III, 1964, which were the artist’s first fully-colored prints) leave the viewer with a feeling of being watched—eyeballs are seemingly everywhere—while simultaneously leading the viewer down mysterious, infinite tunnels.

A threatening quality marks many of the prints, and there are hints of apocalyptic doom. The apocalypse is a theme repeatedly explored by the artist. Between 1967 and 1969, she created flower sculptures made of vacuum-formed plastic that suggest a wasted world. A series of works in the exhibit (Tenth Stone, 1968) features similar types of flowers, their stems screwed together with bolts. Viewed side-by-side, the flowers look to be part of a spare, Mad Max garden. They reflect Bontecou’s concern for the environment.

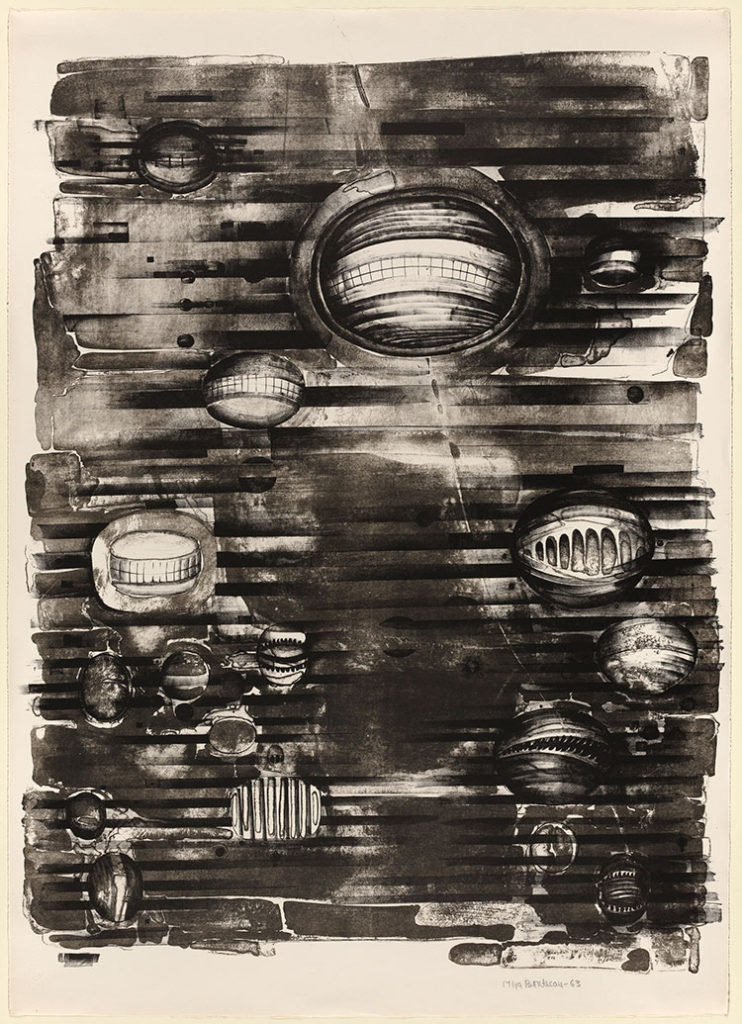

Murky underwater worlds are also on display. A number of pieces feature the artist’s signature weird sea creatures and mollusks. First Stone, 1962, which was the first print Bontecou made, finds the artist experimenting with different symbols and objects. These include sea-things with scary teeth, hard shells, and tendrils floating in aquatic habitats. The largest print Bontecou ever made (An Untitled Print, 1981-82) also suggests a water world. According to exhibit notes, the piece “rivals her sculptures, if only in size.” In person, the creamy, towering, blue-green print has a tumultuous, naked-mermaids-under-the-sea quality. Like Bontecou’s other work, it’s spellbinding.

Third Stone, 1963, finds Bontecou celebrating the freedom that a drawing or a lithograph (as opposed to a sculpture) affords an artist. The exhibit notes for Third Stone include a quote from Bontecou, who says she appreciates the “endless space” that drawings and lithographs allow—“whereas in the sculpture I have to have a frame, something to stop it.” Third Stone is kinetically charged. It can look like a roaring cyclone or a buzzing circular saw. It masterfully illustrates the power of a print.

Meanwhile, in Fourth Stone, 1963—which is related to a series of relief sculptures that Bontecou made in the 1960s—we see the artist adding teeth (clinched, sharp, big, small), blades, and bars to her trademark holes, to creepy effect.

The show offers a peek at various aspects of Bontecou’s process. Her preparatory drawings, stencils, and proofs are on view. We learn about her frustrations and dissatisfactions. She disliked, for instance, the quality of the printing of Eleventh Stone, 1966-70, which is related to a set of colored relief sculptures made in the 1960s. She struggled with the production of Fourteenth Stone, 1968-72, which was the subject of numerous trial and error tests.

In addition to Bontecou’s struggles, we get a look at her routine. The show includes writings by poet Tony Towle, who observed Bontecou during her time working at ULAE. Writes Towle: “Lee would arrive on the ten o’clock train, and work until lunch, and then after lunch until three or four. If she became tired she could take a nap in the yard under the trees, or go swimming, slowly over the surface of the bay in the late afternoon, watching the fish.”

Into the Void features many of Bontecou’s trademark motifs and symbols—sea creatures, menacing teeth, cosmic orbs, apocalyptic flowers—but it’s those perpetually enigmatic voids that dominate the gallery rooms. Fifth Stone, 1964, sums up the illusiveness of the void. Something new is revealed with each viewing: barrels of guns; holes in heads; Cold War-era, prying eyes; telescopic lenses; the vastness of space; the wonder and freedom of the unknown. The voids are everywhere, and they’re both scary and beautiful.

Into the Void: Prints of Lee Bontecou is presented at the Art Institute of Chicago January 26 – May 5, 2019.

Elaine Szewczyk was born in Krakow, Poland. She is a culture writer, an editor, a TV and film script reader, and a novelist. Her novel, I’m with Stupid, was optioned by ABC Studios. She is a voting member of the Writers Guild of America. Follow her at instagram.com/elaineszewczyk.