Now that I am shut in my apartment and far away from everyone else, I am confronted by the limitations of the built environment. I wish there were fewer walls and perhaps an open kitchen; as it stands now, I tend to feel even more confined when I’m inside for too long. I wish there were more windows, more closet space. Whoever designed this building made decisions for me that I’m living with now, and that is the thing: Architecture and design are propositions about how we should live in the future. My building was built 90 years ago, and living here, I am confronted with these original quirks—like the closed-off kitchen and the steam radiator that overheats the space. These old New York buildings were designed in the aftermath of the Spanish Flu pandemic. The city’s Board of Health was convinced that the best cure for the illness was fresh air, so the radiators were designed to keep a house warm in winter with all of the windows wide open. So when it’s cold, I sit here and boil.

These days, I truly have nowhere to be. I’ve lost the ability to plan more than a day or two ahead. For relaxation, I go for walks in my neighborhood, always taking care to keep six feet of distance from people I may cross on the street. I’ve started to notice things I hadn’t before. In normal times, I am almost entirely concerned with buildings for their functions. I don’t experience a bakery or barbershop as a building—it’s where I go to get bread or a haircut. The function doesn’t matter so much anymore; where I would have blindly pushed through those doors in order to quickly get inside, I now find my eyes linger on the details of the exteriors—bricks patterned just so, cornices on the tops of brownstones. I feel that I am seeing many of these aspects for the first time: There is always a difference between familiarity and knowledge, and these formerly familiar things are now becoming known to me.

Inside, I’m watching more films than usual. I often find myself struck by these images of the world as it once was—with restaurants and theaters full, characters standing shoulder-to-shoulder at the bar. They hug and speak inches from each other’s faces, almost certainly spraying microscopic particulates into the shared space. In some ways, seeing their proximity to each other makes me deeply uncomfortable. I’m constantly reminded of what’s been lost these past months; how distant I am from everyone else.

In this state, rewatching Columbus (2017) comes as a relief. It is a strange, subtle, and somewhat confounding film. The characters rarely touch, and they spend so much time looking at buildings instead of each other that the moments of direct eye contact become electric and meaningful. The film is named after its setting: Columbus, Indiana, a little-known town in the Midwest that managed to entice an astonishing number of significant architects to design buildings in the city, often through public-private partnerships. Notable architects include National Academicians Edward Larrabee Barnes (ANA 1969; NA 1974), Edward Charles Bassett (ANA 1970; NA 1990), Romaldo Giurgola (ANA 1982; NA 1994), Richard Meier (ANA 1977; NA 1990), Eliot Noyes (ANA 1967), Nathaniel Alexander Owings (ANA 1961; NA 1967), I. M. Pei (ANA 1963; NA 1965), César Pelli (ANA 1987; NA 1989), James Stewart Polshek (ANA 1983; NA 1994), Kevin Roche (ANA 1976; NA 1973), Eero Saarinen (ANA 1952; NA 1958), Eliel Saarinen (ANA 1940; NA 1946), Robert Venturi (NA 2011), and Harry Mohr Weese (ANA 1965; NA 1975). That so many gorgeous structures could exist in a single town of less than 50,000 is something of a miracle, worth celebrating in its own right, and they are shown throughout the film.

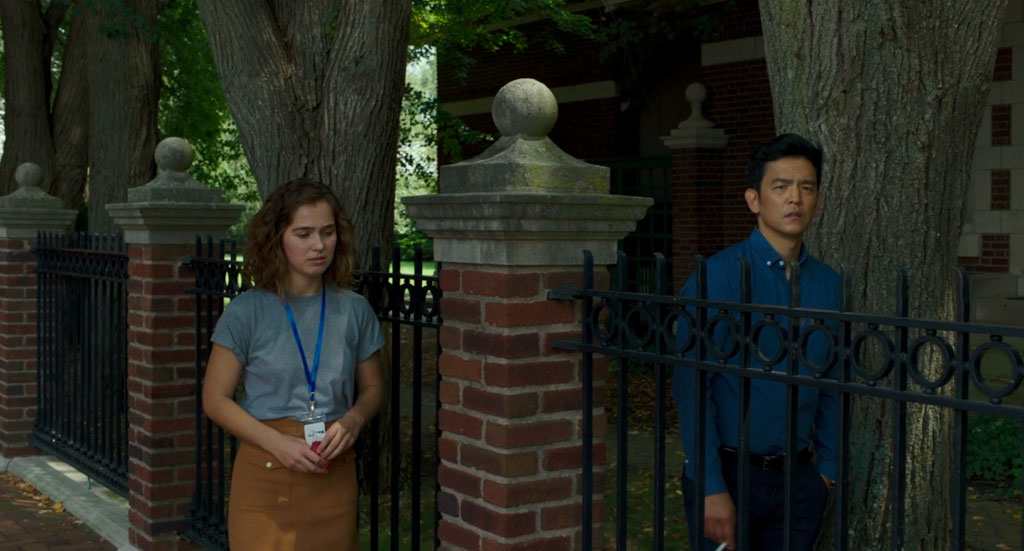

Columbus begins on the periphery of a Modernist masterpiece—Eero Saarinen’s Miller House, 1957. Eliel Saarinen’s First Christian Church, 1942, with its off-centered clock and cross stretching toward each other, is often seen in the background. Fittingly, the two main characters are architecture nerds: Jin (played by John Cho), the son of a distinguished Korean architecture professor, and Casey (played by Haley Lu Richardson), a recent high school graduate, part-time librarian, and occasional tour guide. It is a love story, but this love is almost wholly platonic. Jin and Casey are lonely. They are suffering from their own issues—familial dysfunction and bad luck in love—and they find themselves drawn to each other.

From the moment Jin and Casey meet, their interaction is determined by the built environment: Even their first conversation takes place on opposite sides of a fence. At first, they rarely make eye contact, choosing instead to look at the buildings that surround them. Through their long conversations and meandering walks through the city, they get closer. Instead of completely coming together, the force that binds them seems to simultaneously keep them apart—and so they orbit each other, moving in tandem like planets or stars.

Columbus is the feature-length debut for the director Kogonada, although he has made many short video essays about film. In these works (available on his website and Vimeo channel), he shows a careful attention to the stylistic quirks of auteur cinema, devoting time to studying small details—how Ingmar Bergman employs mirrors, how hands function in Robert Bresson’s work, how Yasujiro Ozu returns to passageways again and again. In Columbus, Kogonada pays homage to Ozu’s subtlety of framing while creating his own visual language. The film makes inanimate objects speak volumes. The repetition of even the smallest detail is not an accident. A three-second shot of an old hat on a green chair, for instance, reverberates far beyond the frame.

There is little plot. The film functions as a series of linked conversations, and the buildings themselves reinforce the thematic content. In the I. M. Pei-designed Cleo Rogers Memorial Library, completed in 1969, Casey talks with a coworker about her generation’s dwindling attention span, and Kogonada shoots at an angle from the ground up, bringing the viewer’s attention to the honeycombed concrete ceiling. In the nave of the painfully exquisite Eero Saarinen-designed North Christian Church, 1964, Jin ponders the fallibility of religious, architectural, and societal institutions. In another scene, Jin and Casey stand outside of the concrete and glass James Polshek-designed Columbus Regional Health Hospital Mental Health Services facility, 1972, and discuss Polshek’s assertion that architecture should primarily be a healing art: that architects should design with a feeling of responsibility for the end user’s well-being. While in another film this dialogue might seem utopic and high-flown, here you get the sense that the characters and the director really believe this. One is reminded of the fact that all these Modernist design decisions were supposed to mean something; that floor-to-ceiling glass, for example, was about transparency and openness. The titans of Modernism hoped their works would bring about a new and better world.

In this near-dystopia—at a time when the next month seems unfathomable, and where the future seems eternally out of reach—where can we find space for utopic thought? In Columbus, Kogonada suggests that a better world can be made through acts big and small. Large scale public works are important, but careful observation, sustained attention, and consideration for the other can have healing powers all on their own. Further still, the film insists that this intimacy and care can come at a slight distance, without romantic coupling.

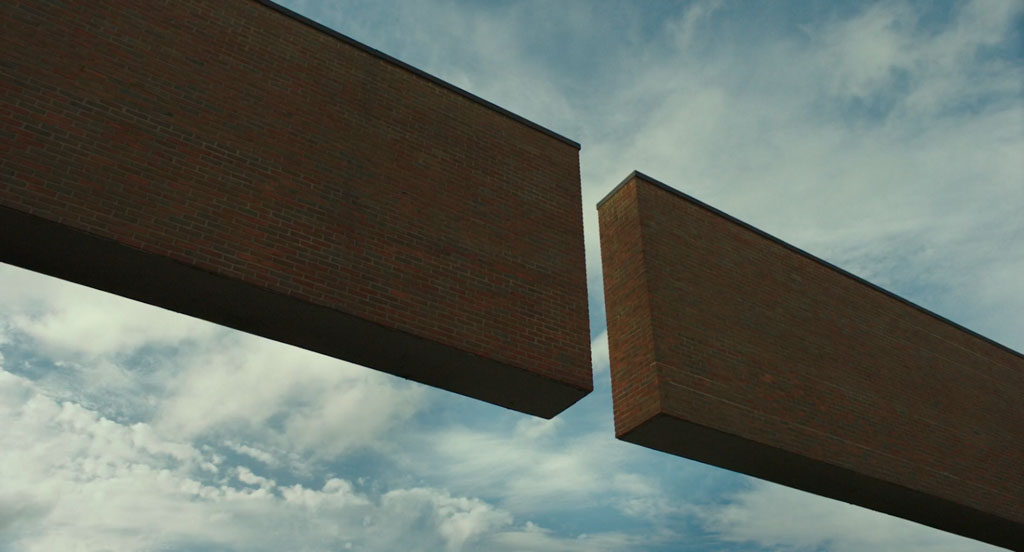

At the Columbus City Hall, 1981, there’s a building designed by Edward Charles Bassett with two cantilevered walls that extend toward each other without meeting. It’s a consistently surprising sight; one’s eye is inevitably drawn to the negative space. Kogonada returns to this building again and again in the film, and it serves as a visual metaphor for the characters: each recognizing a bit of themselves in the other, stretching out toward each other, but remaining wholly separate. In this space—that distance between him and her, you and me, and us and them—we have the ability to make decisions about how to live.

Columbus is available on streaming services.

Coleman Collins is an artist, writer, and athlete from Stone Mountain, Georgia.